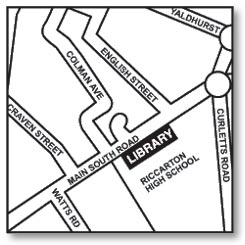

Hanslope Park, where the Foreign Office kept a secret archive of colonial papers. Photograph: Martin Argles for the Guardian

From the Guardian: Thousands of documents detailing some of the most shameful acts

and crimes committed during the final years of the British empire were

systematically destroyed to prevent them falling into the hands of

post-independence governments, an official review has concluded.

Those

papers that survived the purge were flown discreetly to Britain where

they were hidden for 50 years in a secret Foreign Office archive, beyond

the reach of historians and members of the public, and in breach of

legal obligations for them to be transferred into the public domain.

The archive came to light last year when a group of Kenyans detained and allegedly tortured during the Mau Mau rebellion

won the right to sue the British government. The Foreign Office

promised to release

the 8,800 files from 37 former colonies held at the highly-secure

government communications centre at Hanslope Park in Buckinghamshire.

The

historian appointed to oversee the review and transfer, Tony Badger,

master of Clare College, Cambridge, says the discovery of the archive

put the Foreign Office in an "embarrassing, scandalous" position. "These

documents should have been in the public archives in the 1980s," he

said. "It's long overdue." The first of them are made available to the

public on Wednesday at the National Archive at Kew, Surrey.

The

papers at Hanslope Park include monthly intelligence reports on the

"elimination" of the colonial authority's enemies in 1950s Malaya;

records showing ministers in London were aware of the torture and murder

of Mau Mau insurgents in

Kenya,

including a case of aman said to have been "roasted alive"; and papers

detailing the lengths to which the UK went to forcibly remove islanders

from Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean.

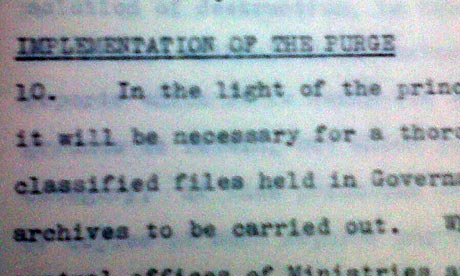

However, among the

documents are a handful which show that many of the most sensitive

papers from Britain's late colonial era were not hidden away, but simply

destroyed. These papers give the instructions for systematic

destruction issued in 1961 after Iain Macleod, secretary of state for

the colonies, directed that post-independence governments should not get

any material that "might embarrass Her Majesty's government", that

could "embarrass members of the police, military forces, public servants

or others eg police informers", that might compromise intelligence

sources, or that might "be used unethically by ministers in the

successor government".

Among the documents that appear to have

been destroyed were: records of the abuse of Mau Mau insurgents detained

by British colonial authorities, who were tortured and sometimes

murdered; reports that may have detailed the alleged massacre of 24

unarmed villagers in Malaya by soldiers of the Scots Guards in 1948;

most of the sensitive documents kept by colonial authorities in Aden,

where the army's Intelligence Corps operated a secret torture centre for

several years in the 1960s; and every sensitive document kept by the

authorities in British Guiana, a colony whose policies were heavily

influenced by successive US governments and whose post-independence

leader was

toppled in a coup orchestrated by the CIA.

The

documents that were not destroyed appear to have been kept secret not

only to protect the UK's reputation, but to shield the government from

litigation. If the small group of Mau Mau detainees are successful in

their legal action, thousands more veterans are expected to follow.

It

is a case that is being closely watched by former Eoka guerillas who

were detained by the British in 1950s Cyprus, and possibly by many

others who were imprisoned and interrogated between 1946 and 1967, as

Britain fought a series of rearguard actions across its rapidly

dimishing empire.

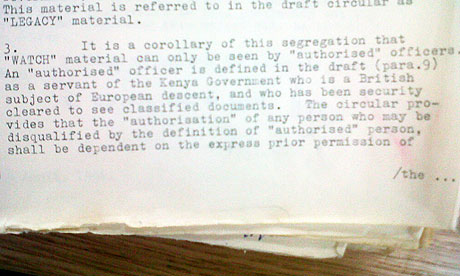

The documents show that colonial officials were

instructed to separate those papers to be left in place after

independence – usually known as "Legacy files" – from those that were to

be selected for destruction or removal to the UK. In many colonies,

these were described as watch files, and stamped with a red letter W.

The

papers at Kew depict a period of mounting anxiety amid fears that some

of the incriminating watch files might be leaked. Officials were warned

that they would be prosecuted if they took any any paperwork home – and

some were. As independence grew closer, large caches of files were

removed from colonial ministries to governors' offices, where new safes

were installed.

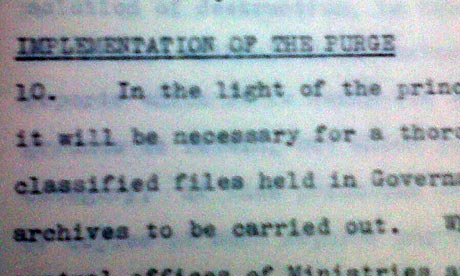

In

Uganda,

the process was codenamed Operation Legacy. In Kenya, a vetting

process, described as "a thorough purge", was overseen by colonial

Special Branch officers.

Painstaking measures were taken to prevent post-independence

governments from learning that the watch files had ever existed. One

instruction states: "The legacy files must leave no reference to watch

material. Indeed, the very existence of the watch series, though it may

be guessed at, should never be revealed."

When a single watch file

was to be removed from a group of legacy files, a "twin file" – or

dummy – was to be created to insert in its place. If this was not

practicable, the documents were to be removed en masse. There was

concern that Macleod's directions should not be divulged – "there is of

course the risk of embarrassment should the circular be compromised" –

and officials taking part in the purge were even warned to keep their W

stamps in a safe place.

Many of the watch files ended up at

Hanslope Park. They came from 37 different former colonies, and filled

200 metres of shelving. But it is becoming clear that much of the most

damning material was probably destroyed. Officials in some colonies,

such as Kenya, were told that there should be a presumption in favour of

disposal of documents rather than removal to the UK – "emphasis is

placed upon destruction" – and that no trace of either the documents or

their incineration should remain. When documents were burned, "the waste

should be reduced to ash and the ashes broken up".

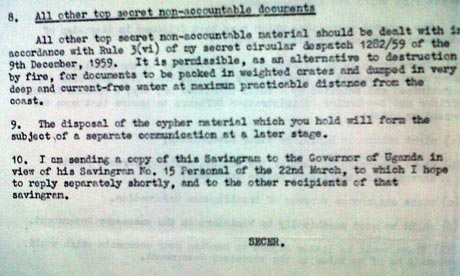

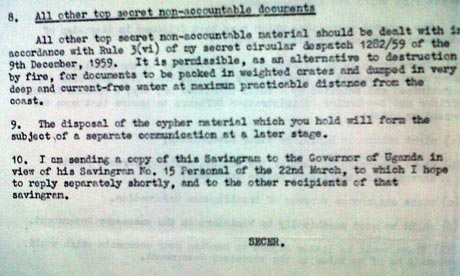

Some idea of

the scale of the operation and the amount of documents that were erased

from history can be gleaned from a handful of instruction documents that

survived the purge. In certain circumstances, colonial officials in

Kenya were informed, "it is permissible, as an alternative to

destruction by fire, for documents to be packed in weighted crates and

dumped in very deep and current-free water at maximum practicable

distance from the coast".