First published in Overland Literary Journal, February 2019.

The writing of history, argued Douglas Hay, ‘is deeply conditioned not only by our personal political and moral histories, but also by the times in which we live, and where we live.’ Whether we acknowledge it or not, all historians and writers ‘take stands by our choice of words, handling of evidence, and analytic categories. And also by our silences.’

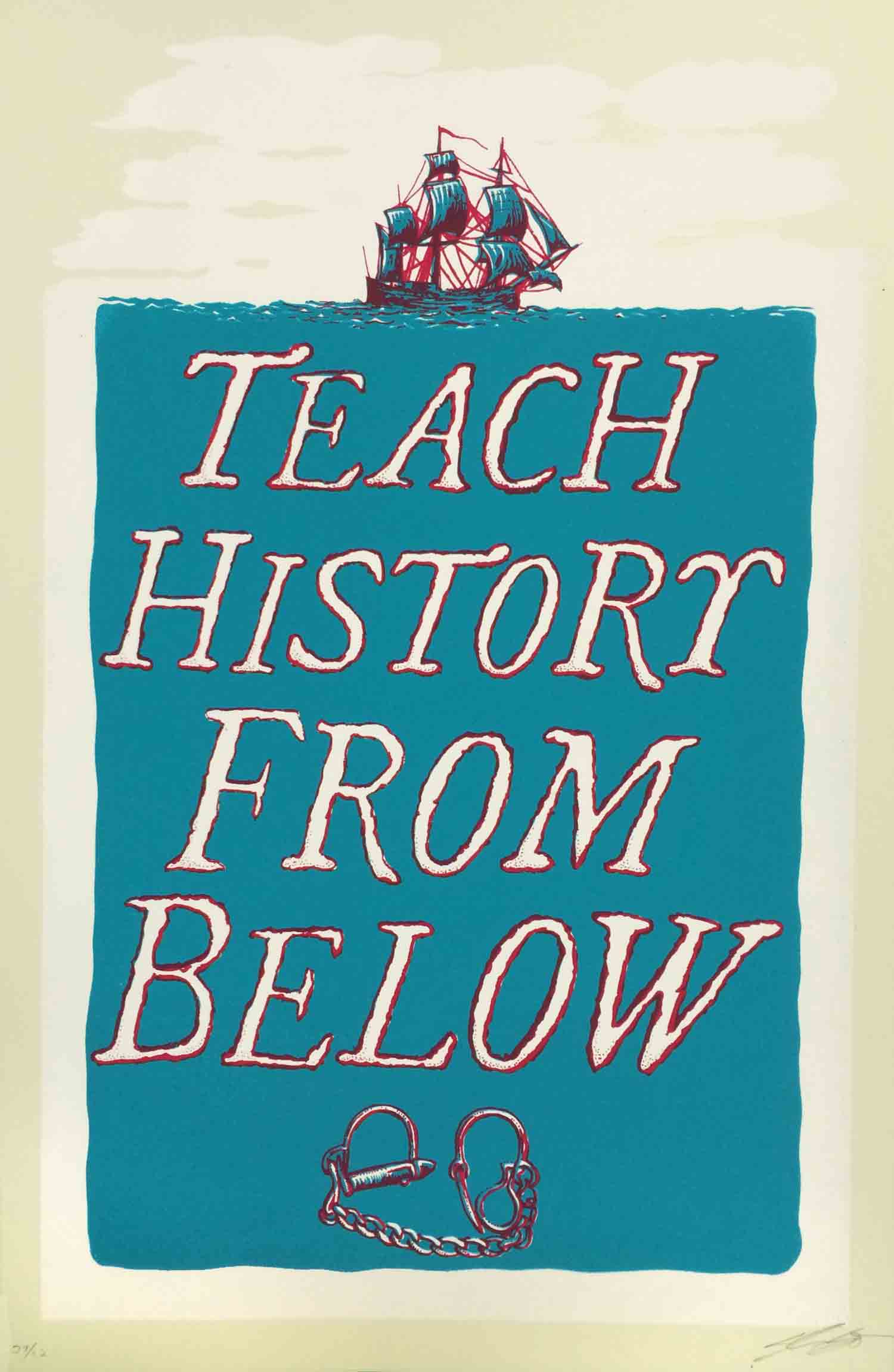

It is these silences – of the historical record and the conscious/subconscious approaches of many historians – that history from below seeks to recover. But what exactly is history from below? Who is below? And now that modern historians of any worth must consider the aims and methods of social history, as well as class, gender and race, is there still value in the label history from below?

Sometimes known as ‘people’s history’ or ‘radical history’, according to the Institute of Historical Research, history from below is history that:

An active and world-renowned practitioner of history from below is Marcus Rediker, Distinguished Professor of Atlantic History at the University of Pittsburgh and author of many prize-winning books (my favourite, by a pinch, is The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic with Peter Linebaugh). For Rediker, history from below is a variety of social history that emerged in the New Left to explore the experiences and history-making power of working people who had long been left out of elite, ‘top-down’ historical narratives. It is an approach to the past ‘that concentrates not on the traditional subjects of history, not the kings and the presidents and the philosophers, but on ordinary working people, not simply for what they experienced in the past but for their ability to shape the way history happens.’ Finding and exalting the collective self-activity or agency of working people is paramount. As Rediker notes, ‘the phrase ‘history from below’ is a rhetorical assertion of political sympathy but also of how history happens.’

It would be wrong, however, to think that history from below ignores power relations or the powerful. As Geoff Eley argues, setting history from below against histories of ‘the bosses, bankers and brokers who run the economy’ is to invoke a false antinomy. ‘Historians from below’, notes Rediker, ‘study power.’

In doing so, history from below (especially feminist work and studies of slavery and unfree labour) has expanded our understanding of the working class and working-class struggle beyond waged labour. Rediker’s own work on slavery and the revolutionary Atlantic is a case in point, for it includes the waged and the unwaged, men and women, and people of many different ethnicities and cultures. Previously overlooked forms of resistance to capitalism have joined the ranks of more traditional labour actions.

Those who have worked to this end includes the American historian Jesse Lemisch, who passed away in late 2018. In his preface to Lemisch’s Jack Tar vs. John Bull: The Role of New York’s Seamen in Precipitating the Revolution, Rediker writes that Lemisch helped to internationalise American history and to make its study more sophisticated ‘by adapting and popularizing the work of the British Marxist historians – Christopher Hill, Eric Hobsbawm, George Rudé, and especially E.P. Thompson, all of whom eschewed dogmatism, reductionism, determinism, and excessive abstraction in favour of a flexible, concrete humanism in the writing of politically-engaged history.’

Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class showed historian Ruth Mather ‘a new way of doing history, one which didn’t patronise working people, or subsume them in a narrative of progress, but instead constructed a story about thinking, feeling people with their own ideas about their lives and their own strategies for living them.’ Rediker argues that Lemisch went beyond these distinguished scholars in several respects:

In this vein, Rediker believes all good storytellers (and good historians) tell a big story within a little story. In his own work ‘the big story has always been the violent, terror-filled rise of capitalism and the many-sided resistance to it from below, whether from the point-of-view of an enslaved African woman trapped in the bowels of a fetid slave ship; a common sailor who mutinied and raised the black flag of piracy aboard a brig on the wide Atlantic; or a runaway former slave who escaped the plantation for a Maroon community in a swamp.’

By emphasising resistance and the agency of everyday people, history from below has always challenged dominant historical narratives and the power relations they help to maintain. Which is why history from below remains as pertinent as ever. As Hitchcock notes, ‘history must be uncomfortable. If history allows you to be complacent, it is not doing its job.’

For Rediker, part of that work is teaching. He is currently the visiting professor at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where he is running the graduate course, ‘How to Write History from Below.’ The course explores the key theories, methods, and issues in history from below, from its origin in the 1930s, through the New Left of the 1960s and 1970s, to the present.

As Marcus prepared for his stint in Hawai’i, he shared online the books that he thought were essential for anyone interested in learning how to write history from below. Thinking they would make a great reading list, I wrote to Marcus and, with his permission, they are reproduced here. They also made me wonder: what books could be considered exemplars of Australian or New Zealand histories from below?

Happy reading!

C.L.R. James, Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution, Vintage, 1938.

‘This powerful, intensely dramatic book is the definitive account of the Haitian Revolution of 1794-1803, a revolution that began in the wake of the Bastille but became the model for the Third World liberation movements from Africa to Cuba.’

E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, Vintage, 1963.

‘A seminal text on the history of the working class by one of the most important intellectuals of the twentieth century … The work has become one of the most influential social commentaries every written.’

Christopher Hill, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas in the English Revolution, Penguin, 1972.

‘Christopher Hill studies the beliefs of such radical groups as the Diggers, the Ranters, the Levellers, and others, and the social and emotional impulses that gave rise to them … It is a portrait not of the bourgeois revolution that actually took place but of the impulse towards a far more fundamental overturning of society.’

Natalie Zemon Davis, The Return of Martin Guerre, Harvard University Press, 1983.

‘Natalie Zemon Davis reconstructs the lives of ordinary people, in a sparkling way that reveals the hidden attachments and sensibilities of nonliterate sixteenth-century villagers.’

Carlo Ginzburg, The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976.

‘An incisive study of popular culture in the sixteenth century as seen through the eyes of one man, the miller known as Menocchio, who was accused of heresy during the Inquisition and sentenced to death … Ginzburg’s influential book has been widely regarded as an early example of the analytic, case-oriented approach known as microhistory.’

Joan Scott, Gender and the Politics of History, Columbia University Press, 1988.

‘This landmark work from a renowned feminist historian is a trenchant critique of women’s history and gender inequality. Exploring topics ranging from language and gender to the politics of work and family, Gender and the Politics of History is a crucial interrogation of the uses of gender as a tool for cultural and historical analysis.’

Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, Autonomedia, 2004.

‘In the neoliberal era of postmodernism, the proletariat is whited-out from the pages of history… Federici shows that the birth of the proletariat required a war against women, inaugurating a new sexual pact and a new patriarchal era: the patriarchy of the wage.’

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, Beacon Press, 2015.

‘Acclaimed historian and activist Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz offers a history of the United States told from the perspective of Indigenous peoples and reveals how Native Americans, for centuries, actively resisted expansion of the US empire.’

Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic, Beacon Press, 2004.

‘Long before the American Revolution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man, a motley crew of sailors, slaves, pirates, laborers, market women, and indentured servants had ideas about freedom and equality that would forever change history … Marshalling an impressive range of original research from archives in the Americas and Europe, the authors show how ordinary working people led dozens of rebellions on both sides of the North Atlantic.’

Marcus Rediker, The Amistad Rebellion: An Atlantic Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom, Penguin, 2012.

‘In this powerful and highly original account, Marcus Rediker reclaims the Amistad rebellion for its true proponents: the enslaved Africans who risked death to stake a claim for freedom.’

Julius Scott, The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution, Verso, 2018.

‘A gripping and colorful account of the intercontinental networks that tied together the free and enslaved masses of the New World… by tracking the colliding worlds of buccaneers, military deserters, and maroon communards from Venezuela to Virginia, Scott records the transmission of contagious mutinies and insurrections in unparalleled detail, providing readers with an intellectual history of the enslaved.’’

It is these silences – of the historical record and the conscious/subconscious approaches of many historians – that history from below seeks to recover. But what exactly is history from below? Who is below? And now that modern historians of any worth must consider the aims and methods of social history, as well as class, gender and race, is there still value in the label history from below?

Sometimes known as ‘people’s history’ or ‘radical history’, according to the Institute of Historical Research, history from below is history that:

seeks to take as its subjects ordinary people, and concentrates on their experiences and perspectives, contrasting itself with the stereotype of traditional political history and its focus on the actions of ‘great men’. It also differs from traditional labour history in that its exponents are more interested in popular protest and culture than in the organisations of the working class.For David Hitchcock, history from below is history which preserves, and which foregrounds, the marginalised stories and experiences of people who, all else being equal, did not get the chance to author their own story. The recovery of voices missing from the historical narrative is a central purpose of history from below.

An active and world-renowned practitioner of history from below is Marcus Rediker, Distinguished Professor of Atlantic History at the University of Pittsburgh and author of many prize-winning books (my favourite, by a pinch, is The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic with Peter Linebaugh). For Rediker, history from below is a variety of social history that emerged in the New Left to explore the experiences and history-making power of working people who had long been left out of elite, ‘top-down’ historical narratives. It is an approach to the past ‘that concentrates not on the traditional subjects of history, not the kings and the presidents and the philosophers, but on ordinary working people, not simply for what they experienced in the past but for their ability to shape the way history happens.’ Finding and exalting the collective self-activity or agency of working people is paramount. As Rediker notes, ‘the phrase ‘history from below’ is a rhetorical assertion of political sympathy but also of how history happens.’

It would be wrong, however, to think that history from below ignores power relations or the powerful. As Geoff Eley argues, setting history from below against histories of ‘the bosses, bankers and brokers who run the economy’ is to invoke a false antinomy. ‘Historians from below’, notes Rediker, ‘study power.’

In doing so, history from below (especially feminist work and studies of slavery and unfree labour) has expanded our understanding of the working class and working-class struggle beyond waged labour. Rediker’s own work on slavery and the revolutionary Atlantic is a case in point, for it includes the waged and the unwaged, men and women, and people of many different ethnicities and cultures. Previously overlooked forms of resistance to capitalism have joined the ranks of more traditional labour actions.

Those who have worked to this end includes the American historian Jesse Lemisch, who passed away in late 2018. In his preface to Lemisch’s Jack Tar vs. John Bull: The Role of New York’s Seamen in Precipitating the Revolution, Rediker writes that Lemisch helped to internationalise American history and to make its study more sophisticated ‘by adapting and popularizing the work of the British Marxist historians – Christopher Hill, Eric Hobsbawm, George Rudé, and especially E.P. Thompson, all of whom eschewed dogmatism, reductionism, determinism, and excessive abstraction in favour of a flexible, concrete humanism in the writing of politically-engaged history.’

Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class showed historian Ruth Mather ‘a new way of doing history, one which didn’t patronise working people, or subsume them in a narrative of progress, but instead constructed a story about thinking, feeling people with their own ideas about their lives and their own strategies for living them.’ Rediker argues that Lemisch went beyond these distinguished scholars in several respects:

If the British Marxist historians, along with the French historians Georges Lefebvre and Albert Soboul, had pioneered ‘history from below,’ which made historical actors of religious radicals, rioters, peasants, and artisans, Lemisch pushed the phrase and the history further and harder with ‘history from the bottom up,’ a more inclusive and comprehensive formulation that brought all subjects, especially slaves and women, more fully into the historian’s field of vision… by insisting that sailors and other workers had ideas of their own, he [also] made a point that many historians have yet to grasp – the history of the working class must be an intellectual as well as a social history.However there is more to it than simply the people we choose to write about (although they are crucial). In researching and telling history from below, the ‘how’ is just as important. This includes the methodologies we use, the sources we scour, and the narratives we employ to tell the story. Eley notes how history from below posits ‘a set of conceptual rules and protocols, methodologies and theoretical approaches, topics and fields, cautions and incitements, that allow the largest of analytical questions to be brought down to the ground.’ Viewpoint is critical. Rediker, echoing George Rawick, notes that ‘if you write something in which an ordinary working person couldn’t see him or herself in that story, somehow you’ve failed. That’s a question of audience, of sympathy, of the subjects you choose to treat, and how you treat them.’

In this vein, Rediker believes all good storytellers (and good historians) tell a big story within a little story. In his own work ‘the big story has always been the violent, terror-filled rise of capitalism and the many-sided resistance to it from below, whether from the point-of-view of an enslaved African woman trapped in the bowels of a fetid slave ship; a common sailor who mutinied and raised the black flag of piracy aboard a brig on the wide Atlantic; or a runaway former slave who escaped the plantation for a Maroon community in a swamp.’

By emphasising resistance and the agency of everyday people, history from below has always challenged dominant historical narratives and the power relations they help to maintain. Which is why history from below remains as pertinent as ever. As Hitchcock notes, ‘history must be uncomfortable. If history allows you to be complacent, it is not doing its job.’

For Rediker, part of that work is teaching. He is currently the visiting professor at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where he is running the graduate course, ‘How to Write History from Below.’ The course explores the key theories, methods, and issues in history from below, from its origin in the 1930s, through the New Left of the 1960s and 1970s, to the present.

As Marcus prepared for his stint in Hawai’i, he shared online the books that he thought were essential for anyone interested in learning how to write history from below. Thinking they would make a great reading list, I wrote to Marcus and, with his permission, they are reproduced here. They also made me wonder: what books could be considered exemplars of Australian or New Zealand histories from below?

Happy reading!

C.L.R. James, Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution, Vintage, 1938.

‘This powerful, intensely dramatic book is the definitive account of the Haitian Revolution of 1794-1803, a revolution that began in the wake of the Bastille but became the model for the Third World liberation movements from Africa to Cuba.’

E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, Vintage, 1963.

‘A seminal text on the history of the working class by one of the most important intellectuals of the twentieth century … The work has become one of the most influential social commentaries every written.’

Christopher Hill, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas in the English Revolution, Penguin, 1972.

‘Christopher Hill studies the beliefs of such radical groups as the Diggers, the Ranters, the Levellers, and others, and the social and emotional impulses that gave rise to them … It is a portrait not of the bourgeois revolution that actually took place but of the impulse towards a far more fundamental overturning of society.’

Natalie Zemon Davis, The Return of Martin Guerre, Harvard University Press, 1983.

‘Natalie Zemon Davis reconstructs the lives of ordinary people, in a sparkling way that reveals the hidden attachments and sensibilities of nonliterate sixteenth-century villagers.’

Carlo Ginzburg, The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976.

‘An incisive study of popular culture in the sixteenth century as seen through the eyes of one man, the miller known as Menocchio, who was accused of heresy during the Inquisition and sentenced to death … Ginzburg’s influential book has been widely regarded as an early example of the analytic, case-oriented approach known as microhistory.’

Joan Scott, Gender and the Politics of History, Columbia University Press, 1988.

‘This landmark work from a renowned feminist historian is a trenchant critique of women’s history and gender inequality. Exploring topics ranging from language and gender to the politics of work and family, Gender and the Politics of History is a crucial interrogation of the uses of gender as a tool for cultural and historical analysis.’

Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, Autonomedia, 2004.

‘In the neoliberal era of postmodernism, the proletariat is whited-out from the pages of history… Federici shows that the birth of the proletariat required a war against women, inaugurating a new sexual pact and a new patriarchal era: the patriarchy of the wage.’

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, Beacon Press, 2015.

‘Acclaimed historian and activist Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz offers a history of the United States told from the perspective of Indigenous peoples and reveals how Native Americans, for centuries, actively resisted expansion of the US empire.’

Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic, Beacon Press, 2004.

‘Long before the American Revolution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man, a motley crew of sailors, slaves, pirates, laborers, market women, and indentured servants had ideas about freedom and equality that would forever change history … Marshalling an impressive range of original research from archives in the Americas and Europe, the authors show how ordinary working people led dozens of rebellions on both sides of the North Atlantic.’

Marcus Rediker, The Amistad Rebellion: An Atlantic Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom, Penguin, 2012.

‘In this powerful and highly original account, Marcus Rediker reclaims the Amistad rebellion for its true proponents: the enslaved Africans who risked death to stake a claim for freedom.’

Julius Scott, The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution, Verso, 2018.

‘A gripping and colorful account of the intercontinental networks that tied together the free and enslaved masses of the New World… by tracking the colliding worlds of buccaneers, military deserters, and maroon communards from Venezuela to Virginia, Scott records the transmission of contagious mutinies and insurrections in unparalleled detail, providing readers with an intellectual history of the enslaved.’’