I thought I would share 'Capitalist-Patriarchy', another section from Maria Mies' excellent book Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women and the International Division of Labour (I transcribed an earlier segment on exploitation/oppression here).

In the book, she lays out the argument outlined below: that capitalism is the latest manifestation of patriarchy, and to see them as separate systems is problematic.

"The reader will have observed that I am using the concept capitalist-patriarchy to denote the system which maintains women's exploitation and oppression.

There have been discussions in the feminist movement whether it is correct to call the system of male dominance under which women suffer today in most societies a patriarchal system. 'Patriarchy' literally means the rule of fathers. But today's male dominance goes beyond 'the rule of fathers', it includes the rule of husbands, of male bosses, of ruling men in most societal institutions, in politics and economics, in short, what has been called 'the men's league' or 'men's house'.

In spite of these reservations, I continue to use the term patriarchy. My reasons are the following: the concept 'patriarchy' was re-discovered by the new feminist movement as a struggle concept, because the movement needed a term by which the totality of oppressive and exploitative relations which affect women, could be expressed as well as their systemic character. Moreover, the term 'patriarchy' denotes the historical and societal dimension of women's exploitation and oppression, and is thus less open to biologistic interpretations, in contrast, for example, to the concept of 'male dominance'. Historically, patriarchal systems were developed at a particular time, by particular peoples in particular geographical regions. They are not universal, timeless systems which have always existed. (Sometimes feminists refer to the patriarchal system as one which existed since time immemorial, but this interpretation is not corroborated by historical, archeological and anthropological research.) The fact that patriarchy today is an almost universal system which has affected and transformed most pre-patriarchal societies has to be explained by the main mechanisms which are used to expand this system, namely robbery, warfare and conquest (see chapter 2).

I also prefer the term patriarchy to others because it enables us to link our present struggles to a past, and thus can also give us hope that there will be a future. If patriarchy had a specific beginning in history, it can also have an end.

Whereas the concept patriarchy denotes the historical depth of women's exploitation and oppression, the concept capitalism is expressive of the contemporary manifestation, or the latest development of this system. Women's problems today cannot be explained by merely referring to the old forms of patriarchal dominance. Nor can they be explained if one accepts the position that patriarchy is a 'pre-capitalist' system of social relations which has been destroyed and superseded, together with 'feudalism', by capitalist relations, because women's exploitation and oppression cannot be explained by the functioning of capitalism alone, at least not capitalism as it is commonly understood. It is my thesis that capitalism cannot function without patriarchy, that the goal of this system, namely the never-ending process of capital accumulation, cannot be achieved unless patriarchal man-woman relations are maintained or newly created...

... Patriarchy thus constitutes the most invisible underground of the visible capitalist system. As capitalism is necessarily patriarchal it would be misleading to talk of two separate systems, as some feminists do. I agree with Chhaya Datar, who has criticized this dualistic approach, that to talk of two systems leaves the problem of how they are related to each other unsolved. Moreover, the way some feminist authors try to locate women's oppression and exploitation in these two systems is just a replica of the old capitalist social division of labour: women's oppression in the private sphere of the family or in 'reproduction' is assigned to 'patriarchy', patriarchy being seen as part of the superstructure, and their exploitation as workers in the office and factory is assigned to capitalism. Such a two-system theory is not capable, in my view, to transcend the paradigm developed in the course of capitalist development with its specific social and sexual divisions of labour. In the foregoing, we have seen, however, that this transcendence is the specifically new and revolutionary thrust of the feminist movement. If feminism follows this path and does not lose sight of its main political goals—namely, to abolish women's exploitation and oppression—it will have to transcend or overcome capitalist-patriarchy as one intrinsically interconnected system. In other words, feminism has to struggle against capitalist-patriarchal relations, beginning with the man-woman relation, to the relation of human beings to nature, to the relation between metropoles and colonies. It cannot hope to reach its goal by only concentrating on one of these relations, because they are interrelated."

Saturday, August 18, 2012

Friday, August 17, 2012

'Sewing Freedom' and early NZ anarchism on Facebook

I've created a Facebook page so that anyone interested can follow the progress of 'Sewing Freedom', my forthcoming book on anarchism in New Zealand. Goodies from the book, pictures, and extra bits of research that never found a home will be shared there. Have a peek and click 'Like': http://www.facebook.com/SewingFreedom

Thursday, August 2, 2012

100 Years On: The Waihi Miners’ Strike

Waihi’s story is history in the present tense…

by Alison McCulloch

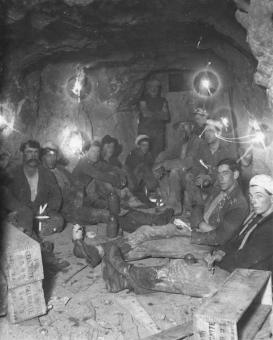

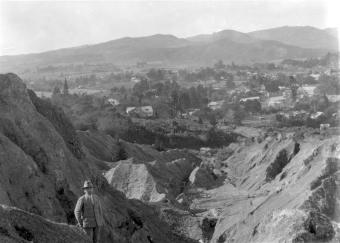

Images of Waihi mining in the 1920s and 30s from “Through the Eyes of a Miner: The photographs of Joseph Divis” by Simon Nathan. (Steele Roberts, 2010) Besides

sitting atop a gold mine, the town of Waihi rests on some political and

economic fault lines that stretch from the present right back to the

town’s European origins. Perhaps the most pivotal event in that history,

aside from the discovery of gold itself, was the miners strike which

began 100 years ago in May and ended six-and-a-half months later, after

the death on 12 November 1912 of one of the strikers, Fred Evans.

Besides

sitting atop a gold mine, the town of Waihi rests on some political and

economic fault lines that stretch from the present right back to the

town’s European origins. Perhaps the most pivotal event in that history,

aside from the discovery of gold itself, was the miners strike which

began 100 years ago in May and ended six-and-a-half months later, after

the death on 12 November 1912 of one of the strikers, Fred Evans.It’s a history that has been much chronicled, studied and disputed. The short version of the strike, and the one given on the Ministry for Culture and Heritage’s NZ History Online, portrays it as a clash between members of a militant Federation of Labour (the so-called Red Feds) and backers of a company-inspired breakaway union for engine-drivers, with some state-sponsored violence thrown in for good measure.

But of course, it’s not that simple. Historians like Jeremy Mouat (in his paper the Ultimate Crisis of the Waihi Gold Mining Company) contend that the duelling unions account understates the role of the company, which was happy to let the Martha mine lie idle “so that it [the company] could come to terms with the mine’s deteriorating position as an ore-producer”. And what about the wider political environment at the time, in particular the circumstance that gave rise to the establishment of the Red Feds in the first place? That’s a part of the story addressed by another historian, Erik Olssen, in his book of the same name, The Red Feds.

The most recent telling of the strike story was written by Mary Carmine, a Waihi local, titled Perspectives of a Strike: Waihi 1912. Carmine, a longtime councillor in Waihi, opens her 112-page book by explaining that she wrote it “for the people of Waihi so that they can know their own history, not be ashamed of it and can understand the actions of their ancestors”.

Carmine’s take definitely has its supporters (it was recommended to me by a spokesman from the current mining company in town, Newmont Waihi Gold, and a Hauraki District Council official) as well as its critics. Among the latter is Joce Jesson, one of the organisers of the Labour History Project’s centenary seminar, scheduled for 10-11 November in Waihi. In a review due to appear in the LHP’s August Newsletter, Jesson applauds Carmine’s bravery in tackling the issue, but sees her book as “the revision of a received truth”.

“Without some sense of significant structures,” Jesson writes, “this work boils down to a trite story about individuals threatening and fighting over what union they should be covered by. There is no sense as to why people were prepared to go to such lengths in defence of the idea of the right to strike, why working with non-union labour was seen as a safety matter, nor what the ultimate goal might be for the strikers.”

Challenging

the “received truth” is one of the goals of the LHP’s November seminar.

As well as a series of papers by New Zealand and Australian historians,

the LHP programme (see a draft schedule below) will be supported by a

series of cultural events, including a “Waihi oratorio” specially

written and directed by South Island playwright Paul Maunder; the launch

of “Gold Strike,” an exhibition by Wellington artist Bob Kerr; and a commemorative ceremony for Fred Evans.

Challenging

the “received truth” is one of the goals of the LHP’s November seminar.

As well as a series of papers by New Zealand and Australian historians,

the LHP programme (see a draft schedule below) will be supported by a

series of cultural events, including a “Waihi oratorio” specially

written and directed by South Island playwright Paul Maunder; the launch

of “Gold Strike,” an exhibition by Wellington artist Bob Kerr; and a commemorative ceremony for Fred Evans.Mark Derby is the chair of the LHP, a non-profit society that works to preserve and promote the history of working life in New Zealand. Derby and the other organisers have made several trips to Waihi in the past year and he says they’re in no doubt that the community feels ambivalent about the impending arrival in their town of academics, political activists and others determined to rake up the ugly and uncertain events of a century ago. He said while the LHP has received support from community leaders, “we’re well aware that some locals would rather we stayed away, and will be happy when this awkward anniversary is safely over and done with”.

Some of the current tensions in town, Derby says, likely date back to those years. It’s not clear how many of the strikers – all of whom were eventually driven from Waihi with the tacit support of the Police – returned to work and settle there, he says, “but I think it likely that those families who can trace their origins back as far as 1912 – and such a pedigree is a source of considerable status in any close-knit community – are most likely to descend from those who opposed the strike, or were at least neutral, rather than those who supported it.”

Back then, the Martha mine one of the world’s greatest, helping to swell the town’s population in 1901 to around 4,000. (It now stands at 4,500.) The year of the strike, Martha produced more than £330,000 worth of gold, down from a peak of £960,000 three years earlier. According to Mouat, a thousand men were working the mine – well over twice the 400-odd workers that today operate not just Martha, but Waihi’s other operations, Trio and Favona.

But going even farther back, before it was the Martha pit, this gold mine was Pukewa – a “broad hill with a pale outcrop of rock … a sacred place,” as Stanley Roche describes it in her book, The Red and the Gold. And that’s another twist in the Waihi saga, one that remains largely invisible in the contemporary disputes about blasting, dust, vibrations, tailings dams, economic stress, depressed property values. The hill is gone, and nothing can bring it back. A 2009 social impact report commissioned by the Newmont noted that the mining of Pukewa “had a significant negative impact on the spiritual connection of local Maori with the land.”

The report went on to quote a comment from one of those researchers interviewed for their study. “There is an emptiness for Maori here in Waihi,” the unidentified resident said.

Remember Waihi – Draft Centenary Seminar Programme

Remember Waihi – Draft Centenary Seminar ProgrammeSaturday 10 November 2012

8.30 am – 12.00 Waihi Community Hall, Seddon St, Waihi

in collaboration with the Australian Mining History Association

Session one

Prelude To The Strike? The 1911 New Zealand Royal Commission on Mines

In the first decade of the 20th century, royal commissions in both Australia and New Zealand sought to deal with growing public and political concerns about their mining industries, especially occupational health and safety issues. The report of the 1911 New Zealand Royal Commission on Mines was the outcome of one of those inquiries, and is an under-utilised source for understanding mining at Waihi in the period immediately prior to the 1912 strike. This presentation is concerned with its narratives from Waihi miners and their union representatives, and its data on fatalities, injuries, and industrial illness. It also focuses on the system of workers’ compensation in the Waihi mining industry around that time, and its significance for industrial relations.

Hazel Armstrong is a Wellington lawyer specializing in employment law and occupational health and safety. She is the author of “Blood on the Coal: The Origins and Future of New Zealand’s Accident Compensation Scheme” (Labour History Project, Wellington, 2008).

Tom Ryan has been a miner and union activist in both Australia and New Zealand, and now teaches anthropology at Waikato University. He has family links to Waihi, as reflected in “The Miners Thumbs: Re-Membering the Past in the Waihi Museum” (NZ Journal of Literature, 2:1, 71-97, 2005).

The Waihi Strike – Some New Evidence

In recent years. the Waihi museum acquired a large and unusual cache of primary documents – letters, telegrams, reports and publications – dealing with the Waihi strike. They formed part of the personal collection of an Auckland unionist closely involved with the strike from the outset and include many documents not previously cited in any published work. This paper examines the historical significance of this collection.

Mark Derby is the chair of the Labour History Project

Striking A Balance – An Oral History of the Waihi Strike

In 2005 Newmont Waihi Gold initiated and funded an oral history project to record the memories of elderly former miners and their families. The interviews have uncovered divergent stories of the same event but it has become obvious that no one involved; the strikers, the ‘scabs’ or the constabulary, were lily white. This presentation uses material obtained from interviews carried out in conjunction with the Newmont Waihi Gold / Waihi Heritage Vision Oral history Project, with descendants of families living in Waihi during the 1912 Waihi Miners’ Strike.

Doreen McLeod is a longterm resident of Waihi and the current manager of Newmont’s interactive visitor centre ‘Waihi’s Gold Story’.

Session two

The 1912 Strike – Casting A Long Shadow Over Waihi

This paper is based on my childhood memories of Waihi in the 1940s. My grandfather had worked at the battery during the 1912 strike and my father often mentioned the strike, which evidently had huge and longlasting implications for the local community. During my early years at school, we learned not to associate with kids whose families still wore the scab label. By contrast, we were required to be ‘good mates’ with the children of the men who were on ‘our side.’ I suspect some kids grew up feeling outcasts – everyone knew they were tainted by their parents’ past.

Peter McAra has worked as a mine truck driver and consultant chemical engineer. He is now a writer, and part-time lecturer at the University of Wollongong

Chasing the Scarlet Runners – Women in Waihi

The women of Waihi played an active and innovative part in the 1912 strike, often stepping well beyond the accepted bounds of female behaviour for that period. Some, known by the admiring name of the ‘scarlet runners’, acted as covert couriers for the strikers, often at considerable personal risk. This paper examines the place of women in Waihi during the most tumultuous events in the town’s history.

Cybele Locke is a lecturer in history at Victoria University. She once played for a social netball team called the Scarlet Runners.

Women’s Voices and Mine Safety

Stanley Roche published The Red and the Gold, an Informal Account of the Waihi Strike in 1984. This book breathed new life into the popular understanding of the Waihi Strike by portraying the strike as a personal and not just a political event. From listening to and recording the voices of the people who experienced the Waihi strike as children, Roche developed the view that history is unreal unless it includes details of day-to-day domestic life, including women’s roles. This paper will trace the research that led Roche to challenge the commonly held view of the women of Waihi as strikebreakers. It will also critically examine the role played by modern day mining companies and unions in ensuring the safety of miners and by association that of their “wives, mothers, and sweethearts”.

Louise Roche is the daughter of Stanley Roche. With Alfred Hill.

12.30- 1 .30 – Lunch – self-catered

1.30 – 5pm Friendship Hall, School Lane, Waihi

Session three

Launch Pad for Waihi: the Forgotten Strike Victory of Wellington’s Tramway Workers

In January 1912, 400 Wellington council ‘trammies’ tapped a growing mood of defiance to arbitration and went on strike over a ‘scab’ inspector. The council capitulated after six days and the NZ Truth newspaper celebrated ‘The Tram Men’s Triumph, What Organised Labour Accomplished.’ This paper argues that this strike victory was a ‘false dawn’ of sorts for the nascent union movement, as the government changed and industrial relations descended into acrimony, even bloodshed, during 1912.

Redmer Yska is a Wellington journalist and historian. His latest book, “The NZ Truth – the rise and fall of the people’s paper,” was published in 2010.

A Tale of Two Strikes- the 1908 Blackball Strike and the 1912 Waihi Strike Compared

The 1908 Blackball coalminers’ and 1912 Waihi goldminers’ strikes were both important events in the Red Fed era of 1908 to 1913; a period of heightened militant industrial action in New Zealand. The Blackball strike was carried out with almost comic opera good humour. There were no scabs, no industrial violence, and no government intervention. Waihi in contrast, resembled the violent strikes taking place in the USA in the same period, with the local workforce and community torn in two. This paper will compare the two strikes, illustrating how the New Zealand industrial and social situation changed from 1908 to 1913. In particular it will look at how the attitudes and aspirations of unionists, employers and government helped create the most dramatic period of class conflict New Zealand has so far experienced.

Peter Clayworth is a Wellington historian. He is writing a biography of miners’ leader Pat Hickey.

The IWW and the Waihi Strike

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was formed in the USA in 1905 with the goal of establishing a socialist society in which workers controlled the means of production. Initially IWW ideas had some influence on the New Zealand Federation of Labour. The Waihi strike, however, bought the differences between the IWW and the NZFL executive to the fore. This paper re-examines the role and influence of IWW philosophies on the miners of Waihi, and argues that they had more support and a bigger influence on the union, individuals and strategies than previously thought.

Stuart Moriarty-Patten recently completed a thesis at Massey University on the IWW in early 20th-century New Zealand.

Session Four

The Aftermath of the 1912 Waihi Strike and the Second Wave of Syndicalism

In 1920, Waihi miners went on strike, and won their demands. In contrast with 1912, both miners and engineers struck, and many strikers left Waihi voluntarily to work temporarily in the Waikato coalfields. This paper questions the common assumption that the repression of workers’ militancy in 1912-13 and during WW1 ushered in a period of moderation and quietude on the industrial front. The 1920 Waihi strike was part of a wider national and international upsurge in class struggle that occurred in New Zealand from 1917 until the early 1920s.

Toby Boraman is a Wellington historian and author of “Rabble rousers and merry pranksters: a history of anarchism in Aotearoa/New Zealand from the mid-1950s to the early 1980s” (2007)

Confrontation and Continuity: Waihi Beyond 1912

Histories of Waihi highlight the passions and significance of the 1912 strike, but typically frame it as a local skirmish in a larger confrontation between the revolutionary ‘Red Feds’ and Massey’s Reform government. Moreover, the involvement of future Labour Cabinet ministers like Bill Parry and Tim Armstrong has encouraged a simplistic view of industrial defeat turning the labour movement towards the ballot box, placing Waihi within a linear political narrative leading to the Labour Party’s 1935 election victory. This focus on leadership and ideology, and conflict rather than continuity, has obscured a more complex history of mining, unionism and local politics in Waihi before and after 1912. By broadening our view of Waihi beyond those few dramatic months a century ago, we can seek to unearth a richer story of labour and life in the gold town.

Neill Atkinson is Chief Historian at Manatū Taonga – the Ministry for Culture and Heritage. A former committee member of the Labour History Project, he has written widely on transport, political and labour history.

Then and Now, There and Here: From Waihi to Western Australia

New Zealand and Australia have long had close connections, with workers, activists and ideas moving between the two lands. These close ties continue in many ways today: at organisational levels, with inter-union ties and multi-national enterprises; at the personal, as workers move between the two countries in search of jobs; and at analytical levels, as scholars and activists learn from one another across the Tasman. One of the major manifestations of these linkages lies in a site as far from New Zealand as one can travel without leaving Australasia, in Western Australia’s booming iron ore mines. Here, many New Zealanders have found work, and some have become leading unionists. Ironically one of the major employers of these men and women is Rio Tinto, whose current anti-union strategies were first honed at the bottom of the South Island of New Zealand, at the Tiwai Point smelter in 1991. This paper is an analysis of contemporary struggles for union survival in iron ore mining. In the course of asking what it is that workers and researchers can learn from history and other places, the importance of the exchange between past and present is highlighted in showing how both employers and unions have sought to use their reading of history as well as local political power, the courts and class alliances to advance their interests.

Bradon Ellem is chair of the Work and Organisational Studies Discipline in the University of Sydney Business School, a Visiting Professor at the Curtin University Graduate Business School and editor, Journal of Industrial Relations.

Friday, July 20, 2012

The Repeal: anti-militarist journal (1913-1914)

Published from March 1913 to August 1914, the Repeal was the journal of the militant Passive Resisters Union, an organization against militarism that formed in Addignton, CHCH in 1912. For a PDF on the PRU click here.

Thursday, July 19, 2012

Some (more) thoughts on activism, class struggle and material needs

In my last post on organization I raised a few points about the idea of organizing around material needs. As I noted in that post, one of the main things Beyond Resistance (BR) wanted to do as a collective was to move beyond an activist approach; to base what we did around the material needs and interests of our members. But what does this actually mean? And what did/would that look like in practice? It's one thing to put such a strategy down on paper, and quite another to make such a strategy a reality.

In this post I want to try and expand on these points. To do this I'll talk a little bit about what we did not want to do (by quoting from articles addressing the problems of activism) and explore the idea of (class) struggle based on material needs and interests. Past activities that I thought the collective did well will be mentioned, and I'll also try to frame what my own personal activity would look like based on these ideas. Again, this is far from new ground, and the ground I'll cover is pretty focused on my own personal and regional sphere. So bear with me as I struggle to write from this personal framework (without sounding trite or individualistic)!

Trying to give up activism...

The experiences of various people in BR, and a text written in 1999 called Give Up Activism, had a huge impact on the scope and activity of our collective. Some of us had been through painful experiences with informal spaces and a lack of accountability/responsibility—'playground anarchism' and 'headless chickenism' were two things we definitely did not want to reproduce. We saw these issues as being the product of an 'activist mentality' (forgive me for the excessive quotes, but they sum it up way better than I could):

"By 'an activist mentality' what I mean is that people think of themselves primarily as activists and as belonging to some wider community of activists. The activist identifies with what they do and thinks of it as their role in life, like a job or career. In the same way some people will identify with their job as a doctor or a teacher, instead of it being something they just happen to be doing, it becomes an essential part of their self-image.The logical result of this leads to single issue actions with little on-going networking (at least not any way that contributes to relationships outside of those in the group/s themselves), and an ideological or moral-based practice. What I mean by this is that struggle can become a battle of ideas: a sort of appeal to the wider world to take action by feeling a sense of outrage, or more positively, through being shown idealised or hypothetical alternatives ("in Spain in 1936, over a million people organised life along anarchist principles... so you should to!"). I don't want to dismiss the role of such arguments. But on their own, or void of a specific context, they often miss their mark (there's plenty of reasons why this happens under and I won't go into them, as it's been said before).

The activist is a specialist or an expert in social change. To think of yourself as being an activist means to think of yourself as being somehow privileged or more advanced than others in your appreciation of the need for social change, in the knowledge of how to achieve it and as leading or being in the forefront of practical struggle to create this change."

"Activism is based on [the] misconception that it is only activists who do social change - whereas of course class struggle is happening all the time"

Instead, I think that people become active/radicalised by events or material conditions that directly affect them (and I don't mean this in a crude economic determinist sense). Explanations that make sense of those experiences often come during, or after, such experiences. Sure, that's a big generalization, but if I think back to my own experience it rings true (after a string of supermarket jobs as a youth, it was the nightshift at an electronics manufacturing plant that prompted me to learn about socialism and Marx. I felt alienation firsthand, and soon realised the cultural privilege I had as a student while my co-workers were overwhelmingly non-pakeha mothers on minimum wage. It was certainly a wake up call).

The activist/moral approach can influence how we view what sites of struggles 'are the most pressing' or 'has the most potential' for social revolution. This can be problematic because it can often lead to us taking the position of the 'outsider' (ie not part of the working class), or place sites of struggle outside of our own lives. We get drawn onto a political/ideological level at the expense of solidarity around lived, material needs (which are shaped by capital, patriarchy etc). This happens even within class struggle circles (although about early SolFed, this quote pretty much sums up early BR):

"So we started doing various ‘class struggle’ things. Going along to picket lines. Writing propaganda about class struggles. Leafletting. We actually had a platformist member at one point who suggested doing a local newsletter and delivering it door-to-door in our areas. We did one issue and abandoned it. We weren’t really happy with the activity of the group, but couldn’t put our finger on why. It felt a lot like activism, only with ‘class struggle’ substituted for GM crops or the arms trade....

Fundamentally, although we were theoretically committed to a ‘politics of everyday life’, our politics had nothing to do with our everyday lives! Class struggle was something that happened to other people. Going down to a picket line at 5am to distro a leaflet was barely any different to going to get on the roof of an arms company or trash a field of GM crops. So we started thinking about whether it could be done better, or whether being in a political group was basically just activism for people with better politics."

Class struggle and material needs

In contrast to an activist approach, an in recognition of relatively low periods of struggle at the moment, people organizing around material needs in their own lives are more likely to lead to the kind of ruptures needed to challenge capitalist relations. Time for another quote:

"Capitalism is based on work; our struggles against it are not based on our work but quite the opposite, they are something we do outside whatever work we may do. Our struggles are not based on our direct needs (as for example, going on strike for higher wages); they seem disconnected, arbitrary. Our 'days of action' and so forth have no connection to any wider on-going struggle in society. We treat capitalism as if it was something external, ignoring our own relation to it."The key for me in this quote is the term 'relation'. It's our relation to capital, our material experience of exploitation (and in turn, what we need to rectify this exploitation) that is important to focus on:

"The struggle then, is to build a revolutionary movement grounded in our everyday lives, which builds working class self-organisation and autonomy, which will require organisation, but which does not become fixated on the building of particular organisations or caught up in its own activity. A movement which realises and constantly reaffirms that we are all involved by nature of our material position in society, and that we who sit through meetings and read about critical theory are not more advanced, nor have more of the answers than those who, probably with good reason, don't take those actions."Now although we in the working class have a shared experience of exploitation on quite a wide level and in various ways (at work, when buying food to survive, renting etc), this fact isn't that helpful in terms of defining a strategy. What might be relevant class struggle to me as a white male could be completely different to the needs of a single mother. Claims that our interests are universal because of our class is not enough. Instead, a focus on the material needs in our own lives—and then trying to organize with others of the same material interests—allows us to concretely identify our lived experience of exploitation and to act in an informed way. In this way form follows content, rather the other way around.

Such an approach recognizes the fact that people will engage in class struggle in various ways and at different sites. For example, as new parents, my partner and I are having very interesting discussions around unwaged work and the reproduction of labour power. That is a site of struggle relevant to my partner's current experience as a mother, and involves a capitalist division of labor informed by patriarchy. Having an understanding of their relationship (or their intersectionality) in material terms, really helps.

Of course if organizing around one's material needs is taken in the strictest sense, there is a danger of limiting oneself to isolated fights or relationships. I guess it's better to think of this approach as a way of beginning; a stepping stone in building relations and circulating struggle amongst similar class interests. As Selma James writes, "to grasp the class interest when there seems not one but two, three, four, each contradicting the other, is one of the most difficult revolutionary tasks, in theory and practice, that confront us." Locating our own struggles as a first step gives us a better chance to grasp these interests.

In practice

Despite the fact that BR never really shed the anarchist propaganda group activity, there were moments when the 'politics of everyday life' approach informed our practice and was put into action. One of the very first major struggles we were involved in was around cuts to public services, when community post offices in a number of communities were scheduled for closure. In this case the community post office of some of our members was due to be shut. A shared interest with their neighbors, and through visible activity in their community, meant those BR members were not outsiders from an outside group. It was based in the everyday lives of the BR members. As a result, our flyers were welcomed, our positions and comments in public forums were listened to with great interest, and I genuinely think we helped to both push aspects of the struggle in more libertarian forms (through calling assemblies and reigning in the power of self-appointed leaders, and by having clear class analysis on why the cuts were happening). Because of this material interest our propaganda had a very real context to draw from, and helped when we started to form connections with other communities in struggle across the city.

In that struggle, BR as an organization worked how I would like to see it functioning now: as a place for comrades to bring their material experience and struggle to the collective in order to discuss, theorize and plan strategy. Part discussion group, part support group, but focused on external praxis in our own lives (although not necessarily as a collective).

So what does that mean for my own material experience of capital, right now? Although I'm a part time-student and mainly a stay-at-home dad at the moment, the most obvious sites of struggle for me to be active in is my workplace and my neighborhood. However I only work one day a week, the workplace itself is small, and a very paternalistic/we're all family culture exists (despite a number of issues that I take note of and talk to co-workers about). Tactically it's probably not the best site of struggle.

That leaves activity in my neighborhood. Where I live is suffering as a result of the Christchurch earthquakes—not in terms of physical damage but through gentrification and massive rent hikes. Rent has jumped by over 26% in the wider city alone, but our proximity to the city has made it a prime location for the development of small businesses and retail. As a result, working people are being driven out in the need for cheaper rental houses. There are community action groups that have been around since the quakes, yet there's also space for a local SolNet or Renters Union. Both options have advantages and disadvantages, but the former would be the easiest to get directly involved in (despite their shortcomings). My biggest hurdle is time—parenting makes what little time I have quite precious and is often filled up with doing things to feel sane (like writing, reading or putting down a brew). It feels selfish writing this, but if I want to be able to sustain struggle in the long-term then I need to think about what I can and can't do at this point in time.

Ultimately, whatever I do, it's unlikely to be very dramatic. Struggling with others around material needs requires a lot more commitment and collective responsibility than most activist campaigns (taking on a shared landlord is not something you'd want to do half-heartedly), so again, maybe now is just not the right time. Nor would it look dramatic: the slow, steady and under-the-radar efforts we need to make with those of shared material interests can often seem like 'doing nothing.' But it's better than 'headless chickenism', and despite bouts of pessimism, surely better than doing nothing at all. As pointed out in this excellent article:

"to do nothing and to think that we must wait for a general upsurge in class struggle, or for 'ordinary workers' to become more radical is in fact to construct a new division between us [with political analysis etc] as a privileged sector that understands struggle and the average worker who does not, but now in reverse of the traditional Leninist vanguard we must deliberately do nothing, rather than lead, because of this division. We have, instead, to see ourselves as part of the working class and that revolutionary activity will only come because of a drive towards that from the working class."

Postscript

After publishing this article, I was asked why I had left out my role as a stay-at-home dad from my current experience. I think this was partly because I saw myself as isolated in this role (I know one other stay-at-home dad); but also because of capitalist-patriarchy, such a struggle isn't given as much time or importance. Considering I've read a bit of James, Della Costa etc, not including this major sphere of my life was pretty shitty.

So when a similar question came up on a listserv I subscribe to, I added some thoughts. Here they are, where they should have been originally.

I take A's question ("Given all the recent talk about critiquing activism, how do you think someone who is a primary caregiver with a toddler can be involved in revolutionary politics?) as: what, if we are to base our activism/struggle/whatever in our everyday life, can a primary care do? As a primary caregiver of a toddler I can definitely relate to this question. In fact, when I didn't mention it in my recent writing I was pulled up by P: I'd described what my workplace or community struggle might look like, but not my material condition as a primary caregiver.

I wonder if this is because there aren't many models to learn from, as traditionally it has been seen as something done next to other political work (ie once you leave the kids somewhere you can then get involved in stuff). Yes, it's becoming more recognised that parenting is a political act and important work. And that childcare is essential for others to join in. But it still seems like that child-raising work is separated from revolutionary politics/class struggle (my article is a case in point). ie parents should come to our struggles and we'll provide a means so that they can (ie childcare), rather than struggling with parents where they're at materially under capitalism.

What if we re-framed the question. For example, as a primary caregiver, how can I organise with others who share the same material interests as me? What would that struggle look like? What could we do to fuck with capitalism in the role assigned to us? Here I think we could learn from the Wages for Housework movement, and ideas around unwaged work and class struggle.

One example they give is how capitalism would grind to a halt if all primary caregivers forced capitalism to deal with the work of caring for children. Child care and schools are just some ways in which capital ensures that children are out of the way so that workers are freed up to continue their dance with capital—to continue to work and be productive. What would happen if we organised other parents, childcare workers and teachers in order to throw a spanner in that? I've read of 'kid-in's' in the UK where caregivers and their children occupied workplaces around issues of care and unwaged work. What would a strike or caregivers look like? Could it be just as effective as shutting down industry, if it forced industry to deal with shitty nappies, screaming babies and reproducing labour?

Interesting to think about, as before I echoed the sentiment of G about class struggle only being in industry and the workplace. Now I think more broadly about class and how capitalism functions, and that's definitely thanks to becoming a parent and reading more radical/marxist feminism : )

Signal 02: Editor's Round Up (from Icky)

After a tough two years (and many gentle reminders from the PM crew) Signal 02 is finally finished. Signal is ongoing project between Josh MacPhee and me, with the aim of documenting international art, graphics, and culture tied to social movements around the world.

Signal 01 had six features: Dutch comix anti-hero Red Rat; graffiti artist Impeach; a photo essay on Adventure Playgrounds; the designer Rufus Segar & Anarchy Magazine; the Taller Tupac Amaru; and posters from the propaganda brigades of Mexico in 1968. With issue 2, we wanted to expand the focus a little and try to cover some new areas and struggles. Here are some highlights:

Røde Mor

A few years back, Josh and I took a rambling trip through Europe trying to collect material for Signal. In Copenhagen, Josh gave a slide-show about political posters including a Danish poster by an (at the time) unknown artist. We were informed that image was made by Dea Trier Mørch, a relatively well-known Danish printmaker who was part of a cultural collective called Røde Mor (Danish for Red Mother). Røde Mor's musical wing, a rock circus/band was quite popular in their time, hitting high in the pop charts and playing festivals. Røde Mor's graphic section made posters for protests, unions, and international struggles. Our hosts played us some of their music, and we were intrigued enough to take a journey to a poster museum in Aarhus that housed (and also sold) a collection of Røde Mor's graphic output. It turned out that the poster museum was in the midst of a historical village (as in re-enactments of old Danish living and industry) and had mostly old cigarette advertisements displayed.

Slightly confused by this, Josh and I took the train back to Copenhagen and the next day, in a book store, stumbled upon some graphic novels and portfolios of Røde Mor's (that was a bit of a running theme of that trip: any effort to actively seek something out met in failure, but luck, curiosity, and greed for books delivered a wealth of new discoveries). At that time, I fell in love with their work.

The graphic novel that I found, BILLEDROMAN, tells three wordless stories from 1973. The first about a Vietnamese woman taking up arms against the Americans, the second about the coup against Allende in Chile, and the third follows a Danish factory worker as she becomes radicalized (the cover image on Signal 02 is from this story). Each story was done by a different artist (Yukari Ochiai, Thomas Kruse, and Dea Trier Mørch, respectively). All were made with one color block prints. Their individual work is distinctive (after a bit of familiarity it's easy to tell who did what), but they feel complimentary to each other. There's also something warm to much of their work. They were attempting to revive the idea of proletarian art; so while the themes are confrontational, advocating revolution, they also feel very inclusive, playful, and sympathetic.

I feel like I shouldn't play favorites within the collective, but I am especially influenced by the work of Dea Trier Mørch, who did the third story mentioned above. Her images are simple with strong line-work, and at the same time highly descriptive & evocative despite their minimalism. She was also a well known author, her most popular book Vinterbørn (Winter's Child, 1976) which she also illustrated, was an experimental feminist novel about childbirth. It was a bestseller and was later made into a film (it is also the only book of hers translated into English, easy to find and cheap).

Kasper Ostrup Frederiksen is an acquaintance of Josh's, a Dane living in England. He also shared a fascination with Røde Mor, and had done some research on them in the past. We contacted him about doing a piece on the collective and he quickly obliged (considering that we're at least a year behind deadline on this issue, I still feel a little guilty with how quickly Kasper got us his piece- sorry Kasper!). It tells the story of the collective as well as having translations of several of their manifestoes, which gives a much rounder view of who they were and what they believed in:

Red Mother is the revolution's mother

The mother of the oppressed, the weak and the orphans

Red Mother waits for you, won't forget you and keeps the food warm

Red Mother is a wild and ferocious lioness

Red Mother walks with an olive branch in its beak

Red Mother is a black sheep and, also, a red flag

Freedom Broadsides

Freedom is an anarchist publication that began in 1886(!). In Signal, we have a collection of old broadsides that we think were used as advertising for new issues of the newspaper. We're not sure where the advertisements were posted, consultation with English anarcho-historians only led to educated speculation (who guessed that maybe they were posted on the sides of news-stands). I like to picture dedicated cadres of street vendors wearing them as sandwich board signs with headlines that read: "Government and The People; Shattering the Dumb Gods," "The Crime of Crimes; Capitalism Condemned," and (my favorite) "All Governments Are Robbers! Why Do You Elect Them?" Most of these date from 1900 to 1910. They work as both a history of the movement and as a fine example of type craft in the early twentieth century.

Josh found these at the Kate Sharpley Library, and when he did, he grunted with delight, which caused me to walk over and see what all the fuss was about.

Oaxacan Street Art in a Mexican Context

We were both eager to get some writing from Deborah Caplow, an art historian, professor, and author in the Pacific NW. I knew of her from her excellent book on Mexican printmaker (and founding member of Taller de Grafica Popular) Leopold Mendez.

Originally Josh and I wanted to see if we could dig a little deeper into the TGP's art process. There are bits of information of how they worked in various books about individual artists within the collective, but the only books on the collective itself are not available in English. Our understanding of their collective practice is that they would decide on general themes and images for a poster as a group, and assign the task to one of the artists within the TGP. The artist would bring back a rough sketch of their idea and it would then be open to collective criticism and adjustment. Sometimes entire works would be redone by different artists within the group. This process, while rare these days, isn't unheard of in art collectives (it is however, ironically, standard practice in commercial/applied art); but at the time (1930s/1940s) this way of working was a pretty wild idea. Josh contacted Deborah and she countered with an article she wanted to do that placed the posters and graffiti that had appeared around the uprising in Oaxaca within a context of Mexican political print making. Which sounded excellent.

Mexican prints, especially Mexican political prints, are very distinctive. There's a richness to the imagery, and often an almost-impossibly skilled use of line work to give the images great depth and movement. Amongst the circle of printmakers that make up Justseeds (the art collective Josh and I are both members of) the influence of the TGP is probably second to none. One of my favorite prints from the TGP starts out this article, Leopold Mendez' Deportacion a la muerte, which is a haunting, high-contrast, print that anguished over the traffic of human lives to the Nazis' death camps in WWII.

The more contemporary work in the article is also quite stunning, most of it done by the collective ASARO. A few years back I saw a presentation by one of the members of this group, who had brought up a pile of prints which had been wheat pasted in the streets of Oaxaca while things there were still quite volatile. My friends and I were blown away by the quality and creativity of the work we saw. The article in Signal shows the strong lineage from Posada to the TGP to these contemporary artists.

The Yamaga Manga

We contacted Keisuke Narita of the Irregular Rhythm Asylum and the Center for International Research on Anarchism in Tokyo about getting some work in this issue from Japan. We didn't have anything in mind in particular and left it open. He sent us various examples of design, old and new, and what jumped out at the time were couple of pages of illustration with narration (comics or manga) painted in muted watercolors. When we expressed an interest in these, Kei informed us that they were made by Taiji Yamaga, a well-known figure in Japanese anarchist and Esperantist circles in Japan, near the end of his life. He made them as a visual reference when he was writing down his memories. They were titled "Sketches From Memory," and they do have a dreamy, staccato flow to them, reminiscent of the ways that memories flow together in bursts.

The narrative covers the tumultuous political life of anarchists in Japan in the early twentieth century. They are beautifully drawn and highly expressive. These were translated by a team in Montreal, led by Adrienne Hurley who has translated other work for PM Press and is also (I believe and hope) working on a history of Japanese Anarchism.

Cranking the Gestetner

Lincoln Cushing wrote a piece about a printing press, the Gestetner, that was popular with radicals in the late 1960s up to the mid-'70s. The Gestetner press could produce pieces that looked better then the low-end mimeographs, could produce faster quantities than hand silk-screening, and was simpler (and less expensive) then a full offset press. This is the back side of art production for political movements, working out how to make things look good, how to make things fast, and how to do it without it dominating your life or forcing you to start a business printing wedding invitations to support printing radical chap-books about free love. The article shows the influence of one old printing technology (Josh originally described the Gestetner to me as an evolutionary dead-end, the cro-magnon of printing presses) and how this technology was used: fully, gleefully, exploited by artists in the movement. Accompanying the article, of course, are several examples of amazing posters made on Gestetner presses.

Malangatana's Fire

Malangatana Valente Nguenha was a Mozambican artist and revolutionary; active and prodcuing art beginning in the 1950s, through the revolution (overthrowing the Portuguese colonizers in 1974), and up to his death in 2011. The article in Signal, we hope, will be one of many covering relatively unknown (in the US) cultural work from Africa.

Malangatana worked in many mediums. We feature mostly his paintings, which are a riot of color, dense, sometimes grotesque, sometimes exuberant. Malangatana was part of a revolution that succeeded and there's an interesting anecdote in the article where he is collaborating with exiled Chilean artists on a mural. Malangatana's work is described as sad and 'anguished', while the Chileans work is hopeful and exhortatory. Malangatana's art was not propaganda (though I respect propagandists, don't get me wrong), but intensely honest. You get the feeling from the article that he felt a great responsibility to be a voice of the people, and it was not his concern how that fit into any particular political platform. He has beautiful line work in his paintings, they flirt with abstraction but doesn't quite go all the way.

The article was written by Judy Seidman who wrote and edited one of the essential books on political poster art: Red On Black: The Story of the South African Poster Movement. She was also a member of the Medu Arts Ensemble and is great artist and poster-maker in her own right.

Revolutionary Portugal

And finally we have piece from PM author Phil Mailer (Portugal: The Impossible Revolution?, about the Carnation Revolution in 1974). Following the revolution, artists and political parties took to the streets in abundance, promoting their own programs or platforms. By 1975 Mailer says that, "there was hardly an unpainted wall anywhere in Lisbon or in the rural towns across the country." The walls were open to any and all to use, so the visible output varied quite a bit. Some of the work is stylized, accomplished, almost slick with its messaging and aesthetic. Other murals are crude and didactic. But all of it (that I've seen, that we have pictures of) is brightly colored, almost exhilarated with possibility. What stands out to me with the Portuguese murals is the seemingly large influence that comics had on their aesthetics. Propaganda from the Eastern Bloc often showed workers as almost superhuman, well rounded men and women with giant hands wielding rifles, ploughs, sickles, and doves. The Portuguese version of the worker is a little different, looking more like Clark Kent in a pair of overalls, or even like Ziggy with an AK47. Anyway, nice stuff and it leaves me hungry to see more.

So that's Signal 02. I think it's a tight issue with a lot of really great content (I'm biased I suppose).

After it's all said and done, there're a few things I notice about this issue. One is that we we're seeking out information about collective work. Part of this, I'm sure, is personal: we both work collectively on art and there's some curiosity about how other folks have made this work in the past. Within our art collective (Justseeds) and in many folks I know there's some trepidation about producing truly collective work. I've described the way that (we believe) the Taller de Grafica Popular operated and people have groaned and sighed, "That sound like a nightmare." I imagine it's a mix of bad experience with collectives (infoshops anyone?), and a perceived idea of Maoist, Orwellian, Weathermen-esque brutal self-criticism sessions. Maybe it's that I know a lot of anarchists or maybe it's that we're Americans, prizing the individual and individual voice. It makes me a little sad to hear those groans as collective work sparks the imagination in ways that are different than individual work. Røde Mor, the TGP, and APPO are great examples of collective work where the individual (the human aspect) is highly visible but it seems to me that work stands stronger due to the connections that are made within the group (both aesthetically and ideologically).

With Signal, we are also seeking out different graphic and aesthetic traditions from around the world. There's something very different about how art and ideas are expressed depending on where it's made, work from Japan and work from the US and work from Mexico are qualitatively different. All cultural expression has different lineages and influences that shape how producers choose to express themselves. With Signal, we are hoping to explore how work is made, why choices were made in output, and what effect the artwork had on a particular movement or struggle (and conversely what effect the movement had on the artwork). As we stated in the intro to Signal:

Art, design, graphics, and culture have been important tools for every social movement that has attempted to challenge the status quo. But not all tools are the same: we don’t use a nail gun to plant a garden, or a rake to fix the plumbing. We hope to broaden the visual discussion of possibility. Social movements have successfully employed everything from print- making to song, theatre to mural painting, graffiti to sculpture. We are internationalists. We are curious about the different graphic traditions and visual languages that exist throughout the world. We feel that broadening our cultural landscape will strengthen the struggle for equality and justice.

Postscript: I wrote this wrap-up to Signal 02 while it was still warm from the printers . . . Josh is out of contact somewhere in the Adirondack Mountains, so the "we" of this blog entry is really an "I", with a speculated (and educated) guess of the thoughts shared by my partner in all this, Josh. Mistakes, suppositions, and assumptions are all mine.

Originally posted on the PM Press Blog

Wednesday, July 11, 2012

Some (more) thoughts on organisation...

It's funny how one's own thoughts can be reflected back at you from the most random places.

The past six months or so have been quite a tough time for me in terms of my politics, or my collective anarchist/community activity. Being busy with life and my son (I'm a stay-at-home dad at the moment while I'm studying part time) means I simply can't get involved in the things that I'd like to right now. A little bit of conflict/change in the anarchist collective I'm involved with, a relatively low period of struggle in Christchurch (despite numerous issues facing the people of this city), and and my own slight burn out/re-evaluation of politics adds to the feeling of confusion and sometimes, outright pessimism.

So when a number of articles on organisation popped up on various websites, it was like finding my doubts manifested and shared. Articles from the US such as some thoughts on political organisation from Juan Conatz (with a valuable comments section), Gayge Operaista’s thoughts on exploitation, repression and self-organisation, and an excellent article on the Cautiously Pessimistic blog summed up a lot of what I had been thinking — the later especially.

It's hard for me to write about organisation at the moment because of my own personal shit (mentioned above) that's tied up with it. I also feel hypercritical writing about it because of these reasons. But I thought I'd record some thoughts nonetheless. They aren't as succinct as the links above, and they mainly relate to my localized experience.

First, a bit of background. I helped get Beyond Resistance (BR) off the ground with a number of anarchists around October 2009. At the time I firmly believed that a tight group of anarchists with a high level of ideological unity was what we needed to forward our political project, which was to get back to long-term workplace/community organising (rather than what we called 'mere reaction'). Whether we were successful with that or not is hard to say. We were involved in lots of projects and events, published some good texts, and were especially active during the initial weeks of the CHCH earthquakes. We helped spread the idea of Solnets in New Zealand (especially through some of our strategy papers and in forums on the West Coast) and started one in Christchurch.

Now, I'm not so sure about the need for a specific anarchist organisation. I've begun to think such groups tend to come at struggle from an ideological place, in terms of appealing to workers on the realm of ideas and morals. Of course we were engaging in struggles around material needs, but I still held to the idea that tighter org will crystalize our arguments, make them sharper and more visible/audible to those in the wider class. Despite arguing that we wanted BR to be based firmly in the struggle around the material needs of our members, we still never shook the mantles of an anarchist propaganda group.

Also, I reckon it's a question of who we work with. In the past I've looked to other anarchists with a similar agreement on principles as my base community. Yet surely this is an arbitrary and unhelpful thing, when compared with say, a community based on material and shared needs? What I mean is something like a Tenants Union of people in my area who share landlords, or as Cautiously Pessimistic points out, those who have a specifically shared experience of exploitation under capital. If class struggle is about building and strengthening relationships and self-activity, why did we as anarchists feel the need to build an anarchist group first, or that to do class struggle we needed a political org behind us — to do it as a political org? I'm not sure if what I'm trying to say makes sense, and maybe it's natural to organize with those you feel closest affinity with. I'm just questioning that particular framework with which we approached struggle.

I'm not anti-organisation, nor have I moved over to a position of pure spontaneity. I definitely think political education and cultural work is needed, and that having a group of peeps you can share your ideas and experiences with is a must: as a place to bounce ideas around practical actions in our lives/struggles. And this is the way BR is starting to operate right now — a place for its members to bring in their experiences of struggle, to discuss and then to put into practice. But at this moment in time, I would rather put any time and energy I had into projects other than an anarchist political project, such as a solnet, or into a tenants union. Only problem is these don't really exist, so building them would be a huge task.

What does that mean for BR? We've decided that the nature of our energy and focus right now means we can't (or won't) do the external stuff we used to do — you know, stuff a typical political org does (propaganda/flyers, evenings, meetings, calling pickets etc). Two years ago I would have slammed such a move as being nothing more than a talk shop; inward-focused and irrelevant. Now I'm not so sure. Groups like Recomposition have been valuable as models, and the discussions on libcom under Juan's text are very interesting (although in CHCH there is no IWW or 'mass' org to 'liquidate' into). I guess we'll just have to wait and see.

The past six months or so have been quite a tough time for me in terms of my politics, or my collective anarchist/community activity. Being busy with life and my son (I'm a stay-at-home dad at the moment while I'm studying part time) means I simply can't get involved in the things that I'd like to right now. A little bit of conflict/change in the anarchist collective I'm involved with, a relatively low period of struggle in Christchurch (despite numerous issues facing the people of this city), and and my own slight burn out/re-evaluation of politics adds to the feeling of confusion and sometimes, outright pessimism.

So when a number of articles on organisation popped up on various websites, it was like finding my doubts manifested and shared. Articles from the US such as some thoughts on political organisation from Juan Conatz (with a valuable comments section), Gayge Operaista’s thoughts on exploitation, repression and self-organisation, and an excellent article on the Cautiously Pessimistic blog summed up a lot of what I had been thinking — the later especially.

It's hard for me to write about organisation at the moment because of my own personal shit (mentioned above) that's tied up with it. I also feel hypercritical writing about it because of these reasons. But I thought I'd record some thoughts nonetheless. They aren't as succinct as the links above, and they mainly relate to my localized experience.

First, a bit of background. I helped get Beyond Resistance (BR) off the ground with a number of anarchists around October 2009. At the time I firmly believed that a tight group of anarchists with a high level of ideological unity was what we needed to forward our political project, which was to get back to long-term workplace/community organising (rather than what we called 'mere reaction'). Whether we were successful with that or not is hard to say. We were involved in lots of projects and events, published some good texts, and were especially active during the initial weeks of the CHCH earthquakes. We helped spread the idea of Solnets in New Zealand (especially through some of our strategy papers and in forums on the West Coast) and started one in Christchurch.

Now, I'm not so sure about the need for a specific anarchist organisation. I've begun to think such groups tend to come at struggle from an ideological place, in terms of appealing to workers on the realm of ideas and morals. Of course we were engaging in struggles around material needs, but I still held to the idea that tighter org will crystalize our arguments, make them sharper and more visible/audible to those in the wider class. Despite arguing that we wanted BR to be based firmly in the struggle around the material needs of our members, we still never shook the mantles of an anarchist propaganda group.

Also, I reckon it's a question of who we work with. In the past I've looked to other anarchists with a similar agreement on principles as my base community. Yet surely this is an arbitrary and unhelpful thing, when compared with say, a community based on material and shared needs? What I mean is something like a Tenants Union of people in my area who share landlords, or as Cautiously Pessimistic points out, those who have a specifically shared experience of exploitation under capital. If class struggle is about building and strengthening relationships and self-activity, why did we as anarchists feel the need to build an anarchist group first, or that to do class struggle we needed a political org behind us — to do it as a political org? I'm not sure if what I'm trying to say makes sense, and maybe it's natural to organize with those you feel closest affinity with. I'm just questioning that particular framework with which we approached struggle.

I'm not anti-organisation, nor have I moved over to a position of pure spontaneity. I definitely think political education and cultural work is needed, and that having a group of peeps you can share your ideas and experiences with is a must: as a place to bounce ideas around practical actions in our lives/struggles. And this is the way BR is starting to operate right now — a place for its members to bring in their experiences of struggle, to discuss and then to put into practice. But at this moment in time, I would rather put any time and energy I had into projects other than an anarchist political project, such as a solnet, or into a tenants union. Only problem is these don't really exist, so building them would be a huge task.

What does that mean for BR? We've decided that the nature of our energy and focus right now means we can't (or won't) do the external stuff we used to do — you know, stuff a typical political org does (propaganda/flyers, evenings, meetings, calling pickets etc). Two years ago I would have slammed such a move as being nothing more than a talk shop; inward-focused and irrelevant. Now I'm not so sure. Groups like Recomposition have been valuable as models, and the discussions on libcom under Juan's text are very interesting (although in CHCH there is no IWW or 'mass' org to 'liquidate' into). I guess we'll just have to wait and see.

Saturday, July 7, 2012

Archives and Activism: Call for Papers

“The rebellion of the archivist against his normal role is not, as so many scholars fear, the politicizing of a neutral craft, but the humanizing of an inevitably political craft."

-- Howard Zinn "Secrecy, Archives, and the Public Interest," Vol. II, No. 2 (1977) of Midwestern Archivist.

The boundaries between "archivist" and "activist" have become increasingly porous, rendering ready distinctions between archivists (traditionally restricted to the preservation of records, maintaining accountability, and making critical information available to the communities they serve) and activists (who, with greater frequency, look to archives or adopt elements of archival practice as a means of documenting their struggles) virtually unsustainable. In the past year, archivists and citizen activists collaborated to document the Occupy Wall Street movement, and archivists committed to open government worked with the New York City Council to advocate for keeping the Municipal Archives as an independent city agency. While the apparent convergence of archival and activist worlds may appear a timely and relevant topic, these distinct communities often deliberate their roles separately with little dialogue.

The Archivists Round Table of Metropolitan New York and the New School Archives and Special Collections are sponsoring a symposium to bring together a diverse group of archivists, activists, students, and theorists with the aim of facilitating discussion of their respective concerns. Among its proposed topics, the symposium will address potential roles that archivists may engage in as activists, as well as how archivists can assume a greater role in documenting and contributing toward social and political change.

Possible areas of interest include, but are not limited to, the following:

-Archivists documenting the work of activists and activist movements

-Activists confronting traditional archival practice

-Possible models for an emergent "activist archives"

-Methodologies for more comprehensively documenting activist

-Archivist and activist collaborations

-Community-led archives and repositories operating outside of the archival establishment

-Archives as sites of knowledge (re)production and in(ter)vention

-Relational paradigms for mapping the interplay of power, justice, and archives

-Critical pedagogy in the reference encounter

-Interrogating preconceptions and misunderstandings that obscure common goals

Date: Friday, October 12, 2012

Location: Theresa Lang Community and Student Center, The New School

All individual presentations will be 20 minutes long (10 page paper).

Submissions must include a title, name of author and institutional affiliation (if applicable), abstract (250 words max), and indication of technological requirements. Individual papers or entire panel proposals accepted.

Deadline for Proposals: Proposals should be emailed to admin@nycarchivists.org by August 1, 2012.

Looks interesting!

Thursday, July 5, 2012

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

anARCHIVE: mock-up of an information retrieval system

The latest assignment for my Masters asked students to create a mock-up information retrieval system (IRS) of a collection of our choosing. It was to take the form of a proposal, and include information on metadata standards, how information about an item (or surrogates in the lingo) is retrieved (such as search, browsing, recall, precision etc) and 10 examples using a wiki or other means to illustrate our IRS in action.

I chose to catalog my zine collection as I'm sure I'll need to do it for Katipo or some other group down the track. It was cool because I got to look at examples of zine libraries around the world and how they cataloged, described and provided access to their zines. I also got to pretend that a functioning anarchist archive in CHCH existed by using a wiki!

Here's my assignment in PDF form, complete with links to 3 example zine collections (Bernard Zine Library, Anchor Archive Zine Library, Salt Lake City Zine Library) and my mock-up IRS, anARCHIVE. I post it because good examples of zine/anarchist archives in practice are hard to find or light on information around how they do things (except for the examples I used, which were great). I also think the metadata fields I came up with are pretty good (although my lecturer suggested I could have used more administrative metadata on when the record itself was created, updated, that sort of thing). Might come in handy for any radical groups out there wanting to catalog their stuff.

View proposal online or download from Issuu:

AnARCHIVE wiki (not an actual archive!)

Saturday, June 23, 2012

Where's the Section on Censorship? A Personal Encounter with Provenance

Some of my writing published by Archifacts October 2011-April 2012 (Journal of the Archives & Records Association of New Zealand).

On the eve of his execution in 1915, Joe Hill—radical songwriter, union organiser and member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)—penned one final telegram from his Utah prison cell: “Could you arrange to have my body hauled to the state line to be buried? I don’t want to be found dead in Utah.”1 After facing a five-man firing squad Hill’s body was cremated, his ashes placed into 600 tiny packets and sent to IWW Locals, sympathetic organizations and individuals around the world. Among the nations said to receive Hill’s ashes, New Zealand is listed.

Yet nothing was known about what happened to the ashes of Joe Hill in New Zealand. Were Hill’s ashes really sent to New Zealand? Or was New Zealand simply listed to give such a symbolic act more scope? If they did make it, what ever happened to them? These were the questions I set about trying to answer late in 2009 as a first-time researcher, initially out of curiosity and then predominantly out of obsession. In the process I published my first book,2 learnt a great deal about the treatment of New Zealand’s radical labour movement during the First World War and gained valuable research skills. I also gained an awareness of the power of archives and the importance of archival theory.

Before I began my research on Joe Hill’s ashes I had only visited an archive once—way back in 2002 as a graphic design student at the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts. Navigating Archway, reference interviews and the concept of provenance therefore, was an entirely new experience. It must have proved fruitful however for I now find myself immersed in a Masters of Information Studies at Victoria University, majoring in archives. The program has given me a theoretical lens into the past, facilitating some interesting reflection about my personal archival interaction. What follows is that reflection: my encounter with archives as a (inexperienced) user, the discovery and use of provenance search methods and grappling with archival gaps.

Joe Hill’s ashes, if they did make it to New Zealand as claimed by a long line of historians, would have arrived by way of post. On 20 November 1916—one year after his execution—Hill’s ashes were given to delegates present at the Tenth Convention of the IWW in Chicago. The remaining packets were then posted around the world on 3 January 1917. According to the minutes of the Chicago Convention, held at Wayne State University, no New Zealander was present. These records, and the fact that the New Zealand IWW had been receiving a steady stream of radical material in the post since 1908, seemed to suggest a postal possibility.

With the help of my friend Mark Crookston—who, at that time, was the Senior Advisor at the Government Digital Archive Programme (Archives New Zealand)—I began to canvas what kind of potential ‘hot spots’ could be present at the National Archives. Discussions with Mark also helped me come to grips with concepts like ‘original order’ and ‘provenance’ and prompted thinking about the postal systems of the past. However my initial experience with the physical archive was accidental. Due to its upgrade the Alexander Turnbull Library had just moved into Archives New Zealand’s Wellington premises—the ever-informative Bert Roth Collection having encouraged me to leave Christchurch and visit the capital. After finishing with the collection early I decided to make use of the Archives New Zealand reference room, and it was here that I experienced the uniqueness of archival principles and the concept of provenance firsthand.

My reference interview at Archives took place early on in my research, so my understanding of the postal system during the war years was still pretty limited. It was also my first archival reference ‘in the flesh’. As part of the Google Generation, my natural approach to Archway and the archivist was that of subject keywords, with a vague notion of their wider context. I quickly realised that simply punching ‘Joe Hill’ into Archway or asking for the ‘postal censorship section’ at the reference desk was not going to cut it. As we discussed my needs the archivist related them to the archive’s series system through looking into the records of the Customs Department. My subject-based enquiry became one of provenance, although I did not understand it fully at the time.

As a new user of archives I found this experience both confusing and fascinating. I had a loose idea of original order and provenance thanks to those late night, kitchen-based discussions with Mark, but I did not realise that description of records would be based on such principles rather than subject. Likewise, employing provenance was a new concept. Thankfully my introduction to archival theory in practice was made a lot easier due to the excellent service I received during that first visit. To cut a long interview short, the result of that experience left me with the seeds of a powerful search method that soon became crucial to my research.

Censorship during the Great War has, unfortunately, been written about very little.4 The lack of information is probably due to the complex system of control put in place by the Massey Government and the confidential nature of its implementation. This confidentiality made an understanding of provenance even more pressing, as structural/functional information was simply not available.

Through the few secondary sources available and many hours on Archway I identified four key players with regard to wartime censorship: the Customs Department, the Post and Telegraph Department, the Army Department, and Sir John Salmond—Solicitor General of New Zealand from 1910-1920. Each was the creator of separate series of records, though provenance (and to an extent the administrative histories provided on Archway) helped make visible the relationships between them.