In this guest post for the Te Papa blog, I ask how historians and others have

measured and defined dissent, sedition and conscientious objection to

military conscription during the Great War. See the original post here.

Socialist Cross of Honour no. 5 awarded to J K Worrall, courtesy of Jared Davidson

To foil the demonstration planned for his release, Wellington jailers

freed William Cornish Jnr an hour early. No matter—his comrades threw

two receptions for him at the Socialist Hall instead. The first, held in

August 1911, saw Cornish Jnr receive a medal from the Runanga

Anti-Conscription League for his resistance to compulsory military

training. The following night he received a second medal (like the one

you can see above)—

the Socialist Cross of Honor.

It is not known how many of these unique medals were produced. By 1913 the

Maoriland Worker had 94 names on their anti-conscriptionist ‘Roll of Honour’ and 7,030 objectors had been prosecuted.

Te Papa holds #29, awarded to E.H Mackie, and at least one more exists in a private collection.

As this and other examples show,

dealing in numbers can be dangerous.

Not only is there endless room for error, we risk being guilty of what

novelist Ha Jin calls the true crime of war: reducing real human beings

to abstract numbers.

[1]

Nonetheless, this post deals with the number of people who objected to

the First World War—those known as conscientious objectors and military

defaulters.

‘Conscientious’ Objection

How we define and count conscientious objectors is inherently

political. For the state, ‘bona fide’ objection was extremely narrow,

limiting it to members of religious bodies that had, before the outbreak

of war, declared military service ‘contrary to divine revelation’.

Defence Minister James Allen and the majority of his colleagues believed

socialist or anti-colonial objection, or anti-authority types who

wanted nothing to do with the state, were not genuine.

More recently, conscientious objection has been limited to men called

up for military service but who explicitly rejected it before an appeal

board. Yet refusing to appear before a board or evading the military

was still a conscious—if less visible—act. Whether we call these men

‘conscientious’ objectors or simply objectors doesn’t change the reality

of their stance. It also misses those not eligible for military

service.

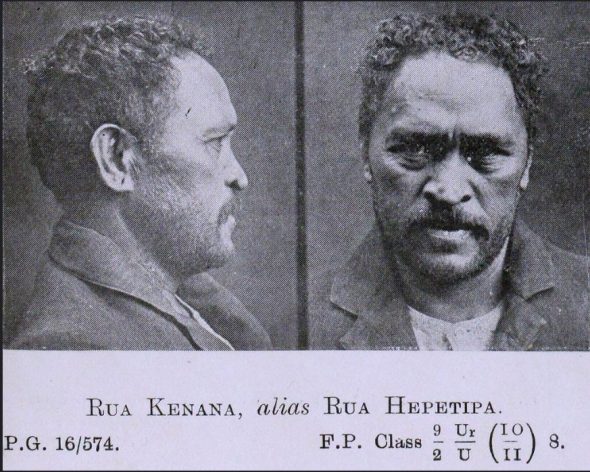

Prophet Rua Kenana was arrested for sedition. Should he be counted as an objector? P12 Box 37/50, Archives NZ

Only 273?

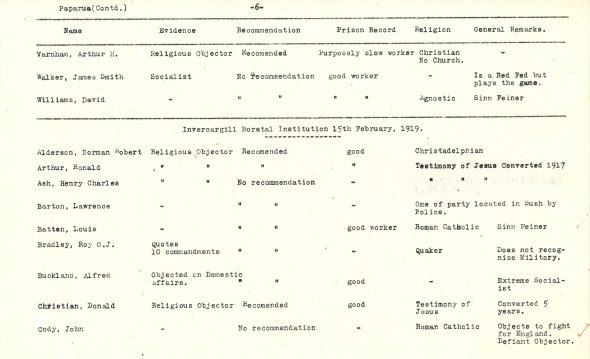

The starting point for most counts is a list compiled in March 1919.

[2]

Initiated by Defence Minister James Allen, it was produced by the

Religious Advisory Board, whose job was to establish which objectors

still in prison were considered genuine and who were not.

Detail from the Religious Objectors Advisory Board list. AD1 Box 743/ 10/407/15, Archives NZ

The Board considered 273 men—

socialists,

Māori,

members of religious sects—and

recommended that 113 religious objectors be left off the military

defaulters list due to be published that year. The remaining 160 were

among the 2,045 defaulters gazetted in May 1919, all of whom lost their

civil rights until 1927. 41 names were added later.

[3]

However the March 1919 list leaves out a large number of objectors

not considered by the Board. Apart from a few exceptions, it does not

include:

- objectors released from prison before March 1919:

comparisons of Army Department returns for 1917-1918 found that at least

28 objectors previously in prison were not on the March 1919 list.[4]

- objectors at Weraroa State Farm, Levin: between 21-28 objectors were interned on 7 January 1918, and a further 32 were due to be sent but never were.[5]

- those who underwent punishment at Wanganui Detention Barracks:

between 8 April 1918 and 31 October 1918, when the camp was shut down

due to the mistreatment of prisoners, 188 men had been processed at

Wanganui.[6] Some, like Irish objector Thomas Moynihan, were eventually coerced into joining the Medical Corps after suffering extreme physical abuse.

- Māori military defaulters: while the 273 includes at least

13 Māori, 89 others were arrested as defaulters. A further 139 were

never found and arrest warrants for 100 of these went unexecuted.[7]

- those convicted for disloyal or seditious remarks: under the War Regulations 287 people were charged, 208 convicted and 71 imprisoned for disloyal or seditious remarks. Only one or two of these are in the Advisory Board report.[8]

This suggests that at least 670 objectors were imprisoned within New Zealand.

Rotoaira Prison for Conscientious Objectors, Waimarino district 1918, J40 Box 202/ 1918/8/6, Archives NZ

Then there are:

- the objectors transported overseas: in July 1917, 14 objectors (including Archibald Baxter and Mark Briggs) were forcibly transported out of the country and subjected to severe punishment.[9]

A further 145 objectors were transported or due to be transported

between December 1917 and August 1918; 74 of these were transported.[10]

- those who served in a non-combatant role: at least 20 objectors were performing non-combatant roles by 31 July 1917.[11]

Between September 1917 and January 1919 a further 176 objectors were

transferred to the Medical Corps at Awanui—161 from Trentham and 15 from

Featherston.[12] Many ended up on hospital ships or the Western Front.

- those who deserted from training camps: historian Paul Baker notes that 430 men deserted between 1917-1918 and 321 remained at large in September 1918.[13] One military publication puts the total number of deserters at 575.[14]

- objectors exempted from military service: at least 73

religious objectors were granted exemption; some of these ended up at

Weraroa Farm or in other non-combatant service.

Historian Paul Baker notes, in his 1988 book about New Zealanders,

conscription and the Great War, that 1,097 defaulters were convicted by

1918 and that 538 were arrested.

[15]

It is hard to know how many of these are included in the numbers above.

But a more accurate number of those who were convicted or came under

state control for wartime objection is somewhere between 1,500, and

2,000 people, with an upper figure of 3,000.

Evading the State

Then there are those who managed to evade the state completely.

Arrest warrants for a further 1133 defaulters were still outstanding at

war’s end, and there were many who never registered with the state in

the first place.

[16] Government statistician Malcolm Fraser estimated that 3,000 to 5,000 men

never registered and couldn’t be conscripted.

[17]

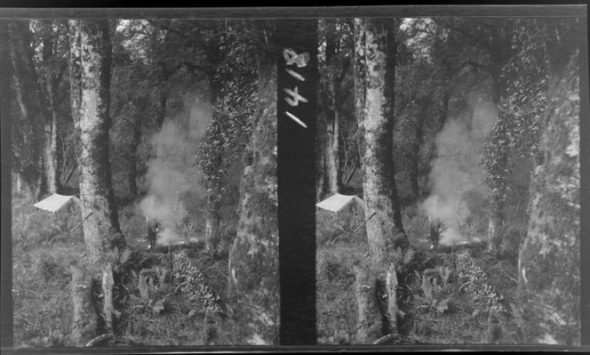

Stereograph

of a camp site in bush area, with unidentified man standing next to

camp fire, West Coast region. Photographed by Edgar Richard Williams.

Ref: 1/2-144082-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

Some of these objectors kept a low profile,

hiding in bush camps

or working on rural back blocks. Others simply left the country. On 11

November 1915, 58 men of military age departed for San Francisco amidst

angry crowds.

[18] As border control tightened objectors were

smuggled out in ship’s coalbunkers by sympathetic seamen—an underground railway of working-class conscripts leaving for less hostile shores.

[19]

Up to six men might be smuggled out per voyage and even if only a few

ships were involved, over several years hundreds may have evaded the

state in this way.

[20]

According to Baker, the number of men who deliberately evaded service and who were never found was between 3,700 and 6,400.

[21] This doesn’t include objectors classified unfit for service like Bob Heffron—later Premier of New South Wales—who

allegedly smoked 12 packs of cigarettes prior to his medical (he was later smuggled to Australia in a ship coal bunker).

When the number of those who evaded the state is added to the number

of objectors convicted or who came under state control, the total figure

is closer to 10,000 (or 5.3% of those eligible for military service).

If we add this to the opposition of those not conscripted or not

eligible to be conscripted—women like

Sarah Saunders Page and

Te Kirihaehae Te Puea Hērangi; anti-militarists like

Carl Mumme;

miners striking against conscription; or

Dalmations resisting state-imposed labour—the figures suggest a significant number of wartime objectors who, for whatever reason, refused to ‘play the game’.

Jared Davidson, June 2016

References

[1] Ha Jin, War Trash, London: Hamish Hamilton, 2004.

[2] ‘Territorial Force – Religious objectors advisory board’, AD1 Box

743/ 10/407/15, Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o Te Kāwanatanga

(ANZ).

[3] Paul Baker, King and Country Call: New Zealanders, Conscription and the Great War, Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1988, p.209.

[4] ‘Returns – Defaulters dealt with under Military Service Act’, AD1

Box 1039/ 64/28, ANZ; ‘Territorial Force – Religious objectors advisory

board’, AD1 Box 734/ 10/407/15, ANZ.

[5] ‘Territorial Force – Employment of religious objectors on State

farms’, AD1 Box 734/ 10/407/2, ANZ lists 21 names, while ‘Weraroa farm

of conscientious objectors’, AD81 Box 5/ 7/14, ANZ records ‘about 28

men’.

[6] ‘Territorial Force – Defaulters undergoing detention and imprisonment’, AD1 Box 738/ 10/566 Parts 1 & 2, ANZ.

[7] Baker, p.220.

[8] Baker, p.167.

[9] ‘Territorial Force – Conscientious objectors sent abroad’, AD1 Box 734/ 10/407/3, ANZ.

[10] ‘Returns – Defaulters dealt with under Military Service Act’, AD1 Box 1039/ 64/28, ANZ.

[11] ‘Territorial Force – Religious and conscientious objectors’, AD1 Box 738/ 10/573, ANZ.

[12] Baker, p.205.

[13] New Zealand Expeditionary Force: its provision and maintenance, p.50.

[14] ‘Territorial Force – Religious objectors return of’, AD1 Box 724/ 10/22/15-20, ANZ.

[15] Baker, p.208; p.75.

[16] ‘Returns – Defaulters dealt with under Military Service Act’, AD1 Box 1039/ 64/28, ANZ.

[17] ‘Military Service Act, 1916 – Military Service Act – Statements

as to probable number who have not registered’, STATS1 Box 32/ 23/1/84,

ANZ. Of the 187,593 who registered, 819 stated religious or

conscientious objections to military service, and a further 260 stated

political objections (although a majority of these favoured

conscription). 1739 did not sate a reason. See Baker, p.58-63.

[18] Baker, p.48.

[19] Conrad Bollinger, Against the Wind: The Story of the New Zealand Seamen’s Union, Wellington: New Zealand Seamen’s Union, 1968, p. 22

[20] Baker, p.204.

[21] Baker, p.208; p.224.