With the centennial of the 1912 Waihi

Strike upon us, this extract seems timely. It is from a letter written

by Leo Woods to Bert Roth, historian and avid creator of (now highly

valued) records pertaining to New Zealand’s labour movement. Roth may

have been collecting material for his book Trade Unions in New Zealand

(Reed, 1973), or for one of many articles and lectures he produced.

Either way, his letter to Woods and subsequent reply offers an insight

into a number of key struggles during the first decades of the twentieth

century—from the Waihi Strike of 1912, to the First World War, the One

Big Union Council and the Communist Party of New Zealand.

Woods was well placed to provide Roth with

the information he sought. Radicalised in the class struggles of 1911

and 1912, he was ‘hunted by the Police in Waihi’, active in the Auckland

branch of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and during the

Great Strike of 1913 sat on the Thames strike committee. As a Wobbly and

socialist, Woods refused to fight during the First World War and was

‘thrown into one of [Prime Minister] Massey’s concentration camps,

Kiangaroa Prison Camp, near Rotorua’ for 18 months. Upon his release in

1919 he was among those who formed the One Big Union Council, becoming

literary secretary and delegated to smuggle banned literature from

Sydney until 1921, when he and other Wobblies formed the Communist Party

of New Zealand. Woods remained a member for over forty years, writing

‘Why I am A Communist’ in 1968.

Written in November 1960, the following

extract is the first four sections of what Woods titled ‘The Labour

Movement’, and is archived in the Roth Collection, MS-Papers-6164,

Alexander Turnbull Library (Wellington).

THE LABOUR MOVEMENT

Waihi Socialist Party

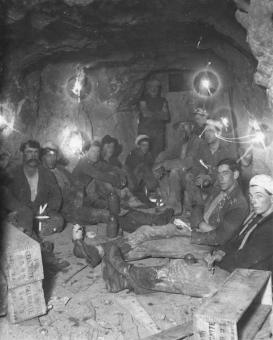

If my memory serves me right in the year

1910, but definitely 1911 and 1912 Waihi boasted the existence of a

Socialist Party, and together with the militant Waihi Miners’ Union

invited socialist and labour leaders near and far, who addressed massed

meetings in the Miners’ Union Hall at the weekends. The first person I

had the honour to listen to was the great socialist leader Tom Mann, who

declared he was a revolutionary socialist. Then followed Ben Tillett

and Alderman [Edward] Hartley. The strike year 1912 attracted more

speakers chief among whom were a person named [Harry] Fitzgerald, a

brilliant orator, and one Jack [John Benjamin] King, a visitor from USA

who [illegible] the principles of the IWW (Industrial Workers of the

World). He formed an economic class on Marxism and delivered several

lectures. He made a great impression on the miners. After he left NZ for

Australia, Prime Minister Massey was going to deport him. Other notable

leaders who came to Waihi were Tom Barker (IWW), H Scott Bennett, great

social reformer and member of Auckland Socialist Party, H E Holland,

Robert Semple, Paddy Webb, Peter Fraser, R F Way and others.

Waihi Strike

In may 1912 the Waihi Miners went on strike

against the action of a section of the union, some but not all of the

engine-drivers in the union breaking away from the union and forming a

‘scab’ union. These boss inspired stooges were used by the mining

companies to smash the militant class-conscious union which had won

concession after concession from the companies in round-table

conferences. Earlier the miners by ballot had discarded the Arbitration

Court as an instrument of the employing class. The mine owners feared

the growing strength of the legitimate union. The strikers fought on for

8 1/2 months, displayed a magnificent spirit of solidarity. The heroism

and pluck of the women folk in standing shoulder to shoulder with the

men was a shining example of courage and dauntless determination. In the

end the strikers were broken by the influx of Premier Bill Massey’s

police thugs who, maddened by liquor (provided by the Tory Government)

batoned the strikers [illegible] and murdered one Frederick George

Evans. Dragged him through the streets and threw him into a prison cell.

He died in hospital a victim of governmental and employers murderous

designs and cruelty, a martyr to the movement of the working class. Many

of the miners were attacked by ‘scabs’ under police protection, and

their property wrecked. Many including myself were forced to leave Waihi

because of the threat of victimisation because we would not be

re-employed. Those who did get back were forced through a searching

screening process. The union President W E Parry and a number of others

were imprisoned because they refused to sign bonds for good behaviour.

But no strike is ever lost because of the spirit of solidarity

manifested and the great boost it gives to trades unionism and the power

and strength it puts into the workers hands. During that strike the

money that was donated by the working class in NZ and Australia ran into

thousands of pounds. That was before capitalistic governments devised

the weapon of freezing union funds.

The General Strike

In 1913 a mass movement of workers staged a

general strike. Watersiders, miners, labourers, seamen, [illegible]

employees and various other trade unions fought for better conditions.

The workers gave the employers the greatest fight of their lives. In the

words of Robert (Bob) Semple Organiser of the Red Federation, that he

would stop the wheels of industry from the North Cape to the Bluff, that

is just about what took place. Labour leaders were again imprisoned.

The ‘Maoriland Worker’ official organ of the Federation of Labour and

the ‘Industrial Unionist’ official organ of the IWW group fought to the

death for the working class, whilst the capitalist press, the Auckland

‘Herald’ and ‘Star’, the ‘Dominion’ and others fought tooth and nail for

their capitalist masters. Once again the money rolled in from

Australian unions and from people who were not on strike in NZ. Strike

committees were set up in strike areas and in non-strike areas alike. In

the latter areas representatives of the strikers spoke and appealed for

funds. In one such area the Thames where a strike committee was set up

with myself as secretary, such speakers as M J Savage (afterwards

Premier of NZ), Ted Canham (Watersiders), Harry Melrose (IWW), Rob Way

and others including local speakers stated the strikers’ case. Once

again the bosses’ stooges formed scab unions. A body (13 men?) could

form a ‘scab’ union and coerce the remainder into joining it. Thus the

strike was again broken. The labour leaders turned to political action,

vote us into power they said and we will legislate for you. You will

never be jailed if you go on strike with a Labour government in power.

But under Prime Minister Peter Fraser (who at one stage led the Waihi

Strike as representative of the Red Federation of Labour) did actually

cause to be jailed ‘[illegible] workers’ who later on went on strike.

How the mighty had fallen!

The IWW

About 1912 a group known as the IWW

(Industrial Workers of the World) was formed in Auckland and other

places in NZ in the most militant areas. Huntly, West Coast of the South

Island, Wellington and elsewhere. The principles of the organization

was the advocacy of Industrial Unionism and the One Big Union. Its

headquarters were in the USA where it had a big following and had very

successful fights with the employing class there. Its preamble went like

this: ‘The working class and the employing class have nothing in

common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among

millions of working people and the few, who make up the employing

class, have all the good things of life. Between these two classes a

struggle must go on until the world’s workers organise as a class, take

possession of the earth and the machinery of production and abolish the

wages system. [illegible] ‘An Injury to one is an injury to all’.

Instead of the conservative motto ‘a fair days wage for a fair days

work’, let us inscribe upon our banner the revolutionary watchword:

abolition of the wages system.’ The IWW did not believe in parliamentary

action. The chief propagandists in the Auckland group were Tom Barker,

Charlie Reeves, Frank Hanlon (Editor of ‘Industrial Unionist’), Allan

Holmes, Jim Sullivan, Bill Murdoch, Percy Short and Jack O’Brien. Lesser

lights but still [illegible] active participation in the struggle were

Frank Johnston, George Phillips, Lila Freeman, myself, just to mention a

few. The aftermath of the 1913 strike and World War 1 scattered the

members far and wide and the group faded away.

— introduced and transcribed by Jared Davidson for Red Ruffians.

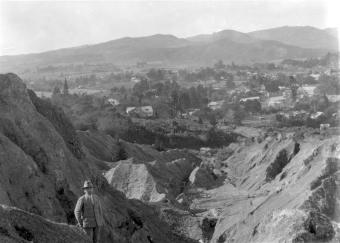

Besides

sitting atop a gold mine, the town of Waihi rests on some political and

economic fault lines that stretch from the present right back to the

town’s European origins. Perhaps the most pivotal event in that history,

aside from the discovery of gold itself, was the miners strike which

began 100 years ago in May and ended six-and-a-half months later, after

the death on 12 November 1912 of one of the strikers, Fred Evans.

Besides

sitting atop a gold mine, the town of Waihi rests on some political and

economic fault lines that stretch from the present right back to the

town’s European origins. Perhaps the most pivotal event in that history,

aside from the discovery of gold itself, was the miners strike which

began 100 years ago in May and ended six-and-a-half months later, after

the death on 12 November 1912 of one of the strikers, Fred Evans. Challenging

the “received truth” is one of the goals of the LHP’s November seminar.

As well as a series of papers by New Zealand and Australian historians,

the LHP programme (see a draft schedule below) will be supported by a

series of cultural events, including a “Waihi oratorio” specially

written and directed by South Island playwright Paul Maunder; the launch

of “Gold Strike,” an exhibition by

Challenging

the “received truth” is one of the goals of the LHP’s November seminar.

As well as a series of papers by New Zealand and Australian historians,

the LHP programme (see a draft schedule below) will be supported by a

series of cultural events, including a “Waihi oratorio” specially

written and directed by South Island playwright Paul Maunder; the launch

of “Gold Strike,” an exhibition by  Remember Waihi – Draft Centenary Seminar Programme

Remember Waihi – Draft Centenary Seminar Programme