Sunday, February 5, 2017

Thursday, October 13, 2016

#HandsOffOurTamariki

Children are being removed from their whānau and dying in alarming numbers. Both Māori and Pākehā children have been killed in unsafe environments, but we only hear of the Māori cases. Māori are then blamed for these deaths and the bad decisions of CYF. This blame has allowed Anne Tolley and the state to ignore the local and international reports about how bad CYF are doing, and how they need to work closer with iwi/hapū. It’s allowed them to create a new Ministry, and strip out the clause for children to remain with iwi/hapū. The end goal is to privatise child care (like what is happening in the UK). This will lead to a ‘care pipeline’ where multi-nationals like Serco profit from the removal and incarceration of Māori.

The ultimate cause of this is colonisation, which attacks Māori so that capitalism can make a profit from the harm that stems from colonisation. It’s a vicious cycle of dispossession and exploitation, and one that is ongoing today. Until Māori are truly in control of their lands, lives and power, it is ridiculous to talk of a post-colonial society. If this is the context, then the struggle for the care of tamariki needs to be a struggle about sovereignty as affirmed in te Tiriti o Waitangi, and as it existed on the ground in this land before 1840.

Further reading is available on the Facebook page, but this article by Kim McBreen is an excellent overview: http://starspangledrodeo.blogspot.co.nz/2016/10/the-nz-state-making-children-vulnerable.html

Friday, September 23, 2016

Domestic Postal Censorship in WWI: RNZ Nights interview

I was lucky enough to have my current research featured on RNZ Nights. From the description:

Not many people know that domestic postal censorship existed - yet from the outbreak of the First World War until November 1920, the private letters of mothers, lovers, internees and workmates were subject to a strict censorship. A team of diligent readers in post offices around the country poured over 1.2 million letters. In some cases, people were arrested and deported because of their private thoughts, or mail was used to hunt down objectors hiding in the bush.You can check out the feature here, or listen below:

There's also a partial transcript on the site.

Wednesday, September 7, 2016

'The Colonial Continuum' wins the 2016 Michael Standish Prize

I am stoked to announce that my paper, 'The Colonial Continuum: Archives, Access and Power' was awarded the 2016 Michael Standish Prize. This award, first offered in 2001, is named in honour of Michael Standish, architect of the 1957 Archives Act and the first permanent Chief Archivist of National Archives. The prize recognises an outstanding essay, by a New Zealand archivist or records manager, dealing with some facet of archives or records administration, history, theory and/or methodology, and published in a recognised archives, records management, or other appropriate journal.

You can read the paper on my blog here, or download a PDF version at academia.edu.

Thank you to everyone who contributed to the paper, who helped look over drafts, and those of you who have shared it, promoted it, or quoted it. It really means a lot and I am thankful for all of your support. And of course, thank you to ARANZ for the recognition of my paper and the generosity you showed me at the Wellington Symposium where it was awarded.

Tuesday, June 28, 2016

Dissent during the First World War: by the numbers

In this guest post for the Te Papa blog, I ask how historians and others have

measured and defined dissent, sedition and conscientious objection to

military conscription during the Great War. See the original post here.

To foil the demonstration planned for his release, Wellington jailers freed William Cornish Jnr an hour early. No matter—his comrades threw two receptions for him at the Socialist Hall instead. The first, held in August 1911, saw Cornish Jnr receive a medal from the Runanga Anti-Conscription League for his resistance to compulsory military training. The following night he received a second medal (like the one you can see above)—the Socialist Cross of Honor.

It is not known how many of these unique medals were produced. By 1913 the Maoriland Worker had 94 names on their anti-conscriptionist ‘Roll of Honour’ and 7,030 objectors had been prosecuted. Te Papa holds #29, awarded to E.H Mackie, and at least one more exists in a private collection.

As this and other examples show, dealing in numbers can be dangerous. Not only is there endless room for error, we risk being guilty of what novelist Ha Jin calls the true crime of war: reducing real human beings to abstract numbers.[1] Nonetheless, this post deals with the number of people who objected to the First World War—those known as conscientious objectors and military defaulters.

‘Conscientious’ Objection

How we define and count conscientious objectors is inherently political. For the state, ‘bona fide’ objection was extremely narrow, limiting it to members of religious bodies that had, before the outbreak of war, declared military service ‘contrary to divine revelation’. Defence Minister James Allen and the majority of his colleagues believed socialist or anti-colonial objection, or anti-authority types who wanted nothing to do with the state, were not genuine.

More recently, conscientious objection has been limited to men called up for military service but who explicitly rejected it before an appeal board. Yet refusing to appear before a board or evading the military was still a conscious—if less visible—act. Whether we call these men ‘conscientious’ objectors or simply objectors doesn’t change the reality of their stance. It also misses those not eligible for military service.

Only 273?

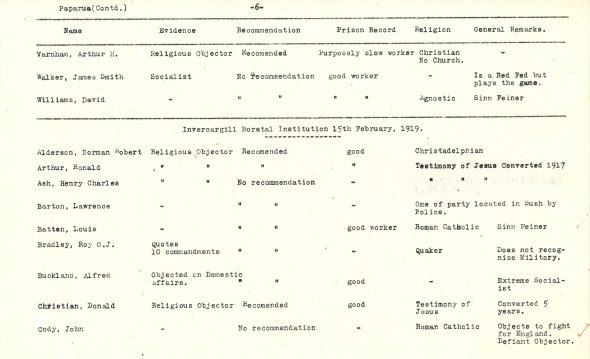

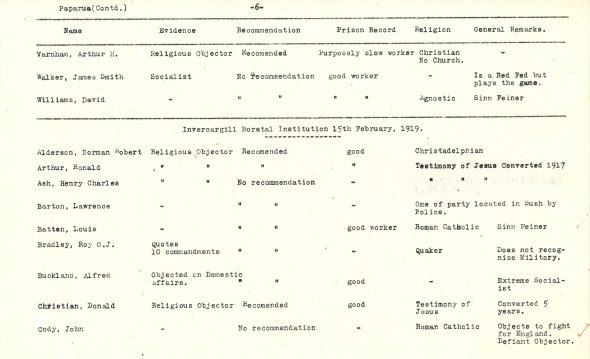

The starting point for most counts is a list compiled in March 1919.[2] Initiated by Defence Minister James Allen, it was produced by the Religious Advisory Board, whose job was to establish which objectors still in prison were considered genuine and who were not.

The Board considered 273 men—socialists, Māori, members of religious sects—and

recommended that 113 religious objectors be left off the military

defaulters list due to be published that year. The remaining 160 were

among the 2,045 defaulters gazetted in May 1919, all of whom lost their

civil rights until 1927. 41 names were added later.[3]

However the March 1919 list leaves out a large number of objectors not considered by the Board. Apart from a few exceptions, it does not include:

Then there are:

Evading the State

Then there are those who managed to evade the state completely. Arrest warrants for a further 1133 defaulters were still outstanding at war’s end, and there were many who never registered with the state in the first place.[16] Government statistician Malcolm Fraser estimated that 3,000 to 5,000 men never registered and couldn’t be conscripted.[17]

Some of these objectors kept a low profile, hiding in bush camps or working on rural back blocks. Others simply left the country. On 11 November 1915, 58 men of military age departed for San Francisco amidst angry crowds.[18] As border control tightened objectors were smuggled out in ship’s coalbunkers by sympathetic seamen—an underground railway of working-class conscripts leaving for less hostile shores.[19] Up to six men might be smuggled out per voyage and even if only a few ships were involved, over several years hundreds may have evaded the state in this way.[20]

According to Baker, the number of men who deliberately evaded service and who were never found was between 3,700 and 6,400.[21] This doesn’t include objectors classified unfit for service like Bob Heffron—later Premier of New South Wales—who allegedly smoked 12 packs of cigarettes prior to his medical (he was later smuggled to Australia in a ship coal bunker).

When the number of those who evaded the state is added to the number of objectors convicted or who came under state control, the total figure is closer to 10,000 (or 5.3% of those eligible for military service). If we add this to the opposition of those not conscripted or not eligible to be conscripted—women like Sarah Saunders Page and Te Kirihaehae Te Puea Hērangi; anti-militarists like Carl Mumme; miners striking against conscription; or Dalmations resisting state-imposed labour—the figures suggest a significant number of wartime objectors who, for whatever reason, refused to ‘play the game’.

References

[1] Ha Jin, War Trash, London: Hamish Hamilton, 2004.

[2] ‘Territorial Force – Religious objectors advisory board’, AD1 Box 743/ 10/407/15, Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o Te Kāwanatanga (ANZ).

[3] Paul Baker, King and Country Call: New Zealanders, Conscription and the Great War, Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1988, p.209.

[4] ‘Returns – Defaulters dealt with under Military Service Act’, AD1 Box 1039/ 64/28, ANZ; ‘Territorial Force – Religious objectors advisory board’, AD1 Box 734/ 10/407/15, ANZ.

[5] ‘Territorial Force – Employment of religious objectors on State farms’, AD1 Box 734/ 10/407/2, ANZ lists 21 names, while ‘Weraroa farm of conscientious objectors’, AD81 Box 5/ 7/14, ANZ records ‘about 28 men’.

[6] ‘Territorial Force – Defaulters undergoing detention and imprisonment’, AD1 Box 738/ 10/566 Parts 1 & 2, ANZ.

[7] Baker, p.220.

[8] Baker, p.167.

[9] ‘Territorial Force – Conscientious objectors sent abroad’, AD1 Box 734/ 10/407/3, ANZ.

[10] ‘Returns – Defaulters dealt with under Military Service Act’, AD1 Box 1039/ 64/28, ANZ.

[11] ‘Territorial Force – Religious and conscientious objectors’, AD1 Box 738/ 10/573, ANZ.

[12] Baker, p.205.

[13] New Zealand Expeditionary Force: its provision and maintenance, p.50.

[14] ‘Territorial Force – Religious objectors return of’, AD1 Box 724/ 10/22/15-20, ANZ.

[15] Baker, p.208; p.75.

[16] ‘Returns – Defaulters dealt with under Military Service Act’, AD1 Box 1039/ 64/28, ANZ.

[17] ‘Military Service Act, 1916 – Military Service Act – Statements as to probable number who have not registered’, STATS1 Box 32/ 23/1/84, ANZ. Of the 187,593 who registered, 819 stated religious or conscientious objections to military service, and a further 260 stated political objections (although a majority of these favoured conscription). 1739 did not sate a reason. See Baker, p.58-63.

[18] Baker, p.48.

[19] Conrad Bollinger, Against the Wind: The Story of the New Zealand Seamen’s Union, Wellington: New Zealand Seamen’s Union, 1968, p. 22

[20] Baker, p.204.

[21] Baker, p.208; p.224.

Socialist Cross of Honour no. 5 awarded to J K Worrall, courtesy of Jared Davidson

To foil the demonstration planned for his release, Wellington jailers freed William Cornish Jnr an hour early. No matter—his comrades threw two receptions for him at the Socialist Hall instead. The first, held in August 1911, saw Cornish Jnr receive a medal from the Runanga Anti-Conscription League for his resistance to compulsory military training. The following night he received a second medal (like the one you can see above)—the Socialist Cross of Honor.

It is not known how many of these unique medals were produced. By 1913 the Maoriland Worker had 94 names on their anti-conscriptionist ‘Roll of Honour’ and 7,030 objectors had been prosecuted. Te Papa holds #29, awarded to E.H Mackie, and at least one more exists in a private collection.

As this and other examples show, dealing in numbers can be dangerous. Not only is there endless room for error, we risk being guilty of what novelist Ha Jin calls the true crime of war: reducing real human beings to abstract numbers.[1] Nonetheless, this post deals with the number of people who objected to the First World War—those known as conscientious objectors and military defaulters.

‘Conscientious’ Objection

How we define and count conscientious objectors is inherently political. For the state, ‘bona fide’ objection was extremely narrow, limiting it to members of religious bodies that had, before the outbreak of war, declared military service ‘contrary to divine revelation’. Defence Minister James Allen and the majority of his colleagues believed socialist or anti-colonial objection, or anti-authority types who wanted nothing to do with the state, were not genuine.

More recently, conscientious objection has been limited to men called up for military service but who explicitly rejected it before an appeal board. Yet refusing to appear before a board or evading the military was still a conscious—if less visible—act. Whether we call these men ‘conscientious’ objectors or simply objectors doesn’t change the reality of their stance. It also misses those not eligible for military service.

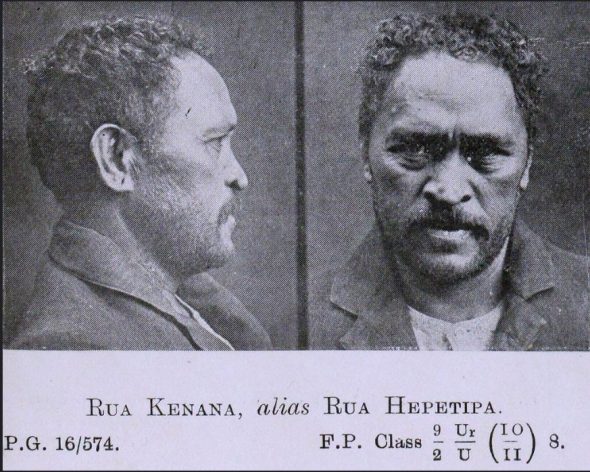

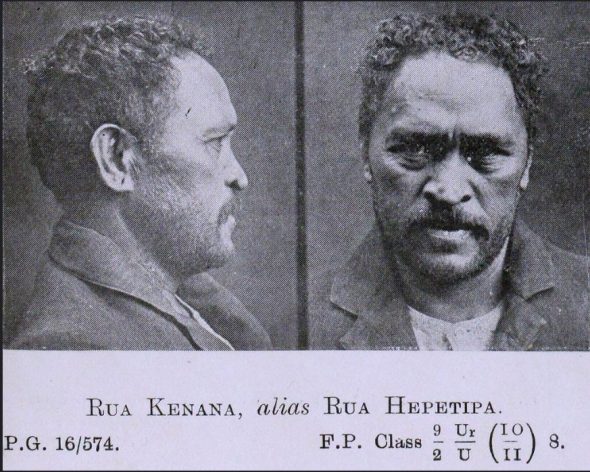

Prophet Rua Kenana was arrested for sedition. Should he be counted as an objector? P12 Box 37/50, Archives NZ

The starting point for most counts is a list compiled in March 1919.[2] Initiated by Defence Minister James Allen, it was produced by the Religious Advisory Board, whose job was to establish which objectors still in prison were considered genuine and who were not.

Detail from the Religious Objectors Advisory Board list. AD1 Box 743/ 10/407/15, Archives NZ

However the March 1919 list leaves out a large number of objectors not considered by the Board. Apart from a few exceptions, it does not include:

- objectors released from prison before March 1919: comparisons of Army Department returns for 1917-1918 found that at least 28 objectors previously in prison were not on the March 1919 list.[4]

- objectors at Weraroa State Farm, Levin: between 21-28 objectors were interned on 7 January 1918, and a further 32 were due to be sent but never were.[5]

- those who underwent punishment at Wanganui Detention Barracks: between 8 April 1918 and 31 October 1918, when the camp was shut down due to the mistreatment of prisoners, 188 men had been processed at Wanganui.[6] Some, like Irish objector Thomas Moynihan, were eventually coerced into joining the Medical Corps after suffering extreme physical abuse.

- Māori military defaulters: while the 273 includes at least 13 Māori, 89 others were arrested as defaulters. A further 139 were never found and arrest warrants for 100 of these went unexecuted.[7]

- those convicted for disloyal or seditious remarks: under the War Regulations 287 people were charged, 208 convicted and 71 imprisoned for disloyal or seditious remarks. Only one or two of these are in the Advisory Board report.[8]

Rotoaira Prison for Conscientious Objectors, Waimarino district 1918, J40 Box 202/ 1918/8/6, Archives NZ

Then there are:

- the objectors transported overseas: in July 1917, 14 objectors (including Archibald Baxter and Mark Briggs) were forcibly transported out of the country and subjected to severe punishment.[9] A further 145 objectors were transported or due to be transported between December 1917 and August 1918; 74 of these were transported.[10]

- those who served in a non-combatant role: at least 20 objectors were performing non-combatant roles by 31 July 1917.[11] Between September 1917 and January 1919 a further 176 objectors were transferred to the Medical Corps at Awanui—161 from Trentham and 15 from Featherston.[12] Many ended up on hospital ships or the Western Front.

- those who deserted from training camps: historian Paul Baker notes that 430 men deserted between 1917-1918 and 321 remained at large in September 1918.[13] One military publication puts the total number of deserters at 575.[14]

- objectors exempted from military service: at least 73 religious objectors were granted exemption; some of these ended up at Weraroa Farm or in other non-combatant service.

Evading the State

Then there are those who managed to evade the state completely. Arrest warrants for a further 1133 defaulters were still outstanding at war’s end, and there were many who never registered with the state in the first place.[16] Government statistician Malcolm Fraser estimated that 3,000 to 5,000 men never registered and couldn’t be conscripted.[17]

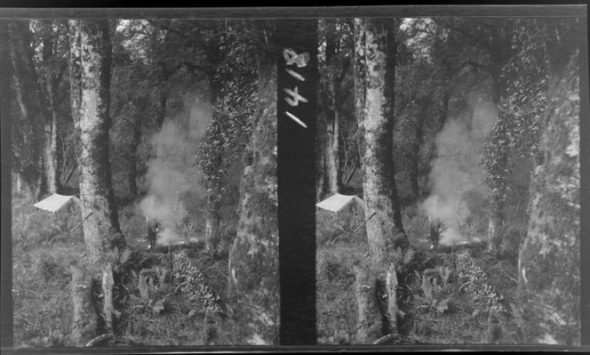

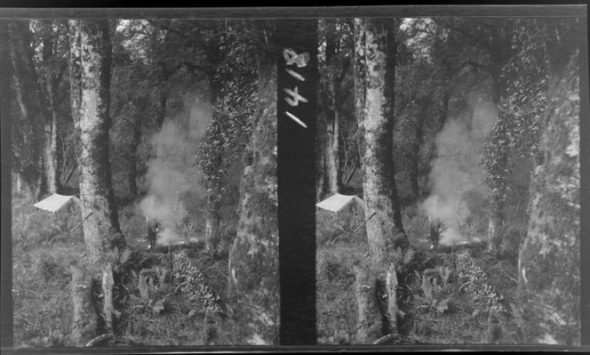

Stereograph

of a camp site in bush area, with unidentified man standing next to

camp fire, West Coast region. Photographed by Edgar Richard Williams.

Ref: 1/2-144082-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

Some of these objectors kept a low profile, hiding in bush camps or working on rural back blocks. Others simply left the country. On 11 November 1915, 58 men of military age departed for San Francisco amidst angry crowds.[18] As border control tightened objectors were smuggled out in ship’s coalbunkers by sympathetic seamen—an underground railway of working-class conscripts leaving for less hostile shores.[19] Up to six men might be smuggled out per voyage and even if only a few ships were involved, over several years hundreds may have evaded the state in this way.[20]

According to Baker, the number of men who deliberately evaded service and who were never found was between 3,700 and 6,400.[21] This doesn’t include objectors classified unfit for service like Bob Heffron—later Premier of New South Wales—who allegedly smoked 12 packs of cigarettes prior to his medical (he was later smuggled to Australia in a ship coal bunker).

When the number of those who evaded the state is added to the number of objectors convicted or who came under state control, the total figure is closer to 10,000 (or 5.3% of those eligible for military service). If we add this to the opposition of those not conscripted or not eligible to be conscripted—women like Sarah Saunders Page and Te Kirihaehae Te Puea Hērangi; anti-militarists like Carl Mumme; miners striking against conscription; or Dalmations resisting state-imposed labour—the figures suggest a significant number of wartime objectors who, for whatever reason, refused to ‘play the game’.

Jared Davidson, June 2016

References

[1] Ha Jin, War Trash, London: Hamish Hamilton, 2004.

[2] ‘Territorial Force – Religious objectors advisory board’, AD1 Box 743/ 10/407/15, Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o Te Kāwanatanga (ANZ).

[3] Paul Baker, King and Country Call: New Zealanders, Conscription and the Great War, Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1988, p.209.

[4] ‘Returns – Defaulters dealt with under Military Service Act’, AD1 Box 1039/ 64/28, ANZ; ‘Territorial Force – Religious objectors advisory board’, AD1 Box 734/ 10/407/15, ANZ.

[5] ‘Territorial Force – Employment of religious objectors on State farms’, AD1 Box 734/ 10/407/2, ANZ lists 21 names, while ‘Weraroa farm of conscientious objectors’, AD81 Box 5/ 7/14, ANZ records ‘about 28 men’.

[6] ‘Territorial Force – Defaulters undergoing detention and imprisonment’, AD1 Box 738/ 10/566 Parts 1 & 2, ANZ.

[7] Baker, p.220.

[8] Baker, p.167.

[9] ‘Territorial Force – Conscientious objectors sent abroad’, AD1 Box 734/ 10/407/3, ANZ.

[10] ‘Returns – Defaulters dealt with under Military Service Act’, AD1 Box 1039/ 64/28, ANZ.

[11] ‘Territorial Force – Religious and conscientious objectors’, AD1 Box 738/ 10/573, ANZ.

[12] Baker, p.205.

[13] New Zealand Expeditionary Force: its provision and maintenance, p.50.

[14] ‘Territorial Force – Religious objectors return of’, AD1 Box 724/ 10/22/15-20, ANZ.

[15] Baker, p.208; p.75.

[16] ‘Returns – Defaulters dealt with under Military Service Act’, AD1 Box 1039/ 64/28, ANZ.

[17] ‘Military Service Act, 1916 – Military Service Act – Statements as to probable number who have not registered’, STATS1 Box 32/ 23/1/84, ANZ. Of the 187,593 who registered, 819 stated religious or conscientious objections to military service, and a further 260 stated political objections (although a majority of these favoured conscription). 1739 did not sate a reason. See Baker, p.58-63.

[18] Baker, p.48.

[19] Conrad Bollinger, Against the Wind: The Story of the New Zealand Seamen’s Union, Wellington: New Zealand Seamen’s Union, 1968, p. 22

[20] Baker, p.204.

[21] Baker, p.208; p.224.

Thursday, June 9, 2016

'Fighting War: Anarchists, Wobblies & the New Zealand State 1905-1925' now available

Fighting War: Anarchists, Wobblies & the New Zealand State 1905-1925 is now available from https://www.rebelpress.org.nz/publications/fighting-war

Using government archives and contemporary publications, this pamphlet unearths the story of some of the men and women in Aotearoa New Zealand who opposed the state, militarism, and a world at war.

Anarchists, ‘Wobblies’ (members of the Industrial Workers of the World) and their supporters did not stand against militarism because they were pacifists, but as members of the working class who refused to fight working class people from other countries. For them the world was their country; their enemy was capitalism. Their fight for a free society led to an intense cultural struggle—one that questioned the war, the nature of work and authority itself. This battle for minds had material results. Intense state surveillance and a raft of legislation not only deter- mined who could read what, but led to jail time or deportation from the country. In a time of smothering oppression and social pressures, they held on to their beliefs with courage, ingenuity and resolve.

Published by Rebel Press.

| Author: | Jared Davidson |

| Release Date: | May 2016 |

| Dimensions: | 148mm x 210mm |

| Pages: | 33 |

| Binding: | Stapled and folded |

| ISBN: | 978-0-473-35388-9 |

Wednesday, May 18, 2016

Voices Against War: new website on conscientious objection

|

| "Bob Semple release from prison,” Voices Against War, accessed May 18, 2016, http://www.voicesagainstwar.nz/items/show/65 |

What I like about the website is its inclusion of women and pre-war anti-militarism. In most accounts, conscientious objection seems to fall out of the sky after the Military Service Act was passed in August 1916. Yet as the website (and my own work) shows, 1916-1918 objection was the continuation of resistance that had been temporarily submerged by the initial fervor of war. By including women, the website also widens the picture of wartime dissent—more often than not portrayed as the domain of those men eligible for military service only.

From the site:

When the New Zealand Government announced it was joining Britain in the war against Germany in August 1914, most New Zealanders greeted the news with wild enthusiasm. Volunteers flocked to enlist. It took real courage to go against this feverish tide of opinion but a few brave voices spoke out for peace.I encourage you to take a peek, browse the stories, or scroll through the goodies on offer.

Hundreds of young men chose to go to prison as objectors to conscription rather than compromise their beliefs, both in the pre-war period when compulsory military training was introduced and during the war.

On this website we highlight the stories of some of those courageous individuals who became political prisoners during this tumultuous period. Some served time in the old Lyttelton Gaol, some in the new prison at Paparua and others endured military detention in Fort Jervois on Ripapa Island.

Public sentiment was against the objectors. Usually referred to as ‘shirkers’, they suffered vilification at the hands of the press, discrimination in their workplaces, and in some cases the loss of civil rights for up to ten years. By also telling the story of the anti-militarist movement that began in Christchurch in 1910 we are marking the origins of the Pakeha peace movement in Aotearoa New Zealand. The labour movement was almost wholly anti-militarist and we also tell the story of those men jailed for breaching the government regulations that said it was sedition to speak out against conscription or war.

Women were not directly involved in compulsory military training or conscription, but some were involved in the anti-militarist organisations. They supported the men who were taking a stand, while also taking a courageous stand themselves to uphold what they saw as the British tradition of freedom of conscience. Maori were initially exempted from conscription. Later the Act was amended to include Maori though conscription was imposed only on Tainui Māori.

In telling these stories, many of which have not been told before, we are not seeking to dishonour or detract from the bravery and commitment to duty displayed by the thousands of men who served in the New Zealand expeditionary force. But these stories of Canterbury’s forgotten history have a place too and are an important part of Aotearoa New Zealand’s response to the First World War.

Friday, April 22, 2016

Hot off the press!

Hot of the (Rebel) Press! My latest little text in time for #AnzacDay2016. Ta @anarchobooks! @AKPressDistro #WW1 pic.twitter.com/FElXcTBRHj— Jared Davidson (@anrchivist) April 22, 2016

Monday, February 29, 2016

Unschooling Camp, Foxton Beach 2016

Our whānau has just returned from a four-day camp for those who unschool or practice natural/child-led learning. Held at Foxton Beach Boys Brigade, it was a great space and an amazingly inspiring time. Best of all, it confirmed for me that exploring the possibility of unschooling could be the right choice for our children (or should I say, they have made the right choice themselves!)

We've been investigating/doing unschooling with our six year-old for a year now, but really the last year has been a continuation of our parenting style/philosophy and the holistic approach that we learned through Playcentre. In a wiki nutshell unschooling is:

an educational method and philosophy that advocates learner-chosen activities as a primary means for learning. Unschooling students learn through their natural life experiences including play, household responsibilities, personal interests and curiosity, internships and work experience, travel, books, elective classes, family, mentors, and social interaction. Unschooling encourages exploration of activities initiated by the children themselves, believing that the more personal learning is, the more meaningful, well-understood and therefore useful it is to the childLike the idea of anarchism, this does not mean no rules, structure or organisation—far from it! We've actively developed an educational practice to suit our eldest child that we constantly document and review. But it does mean not going to school, which for many is a radical concept. (I'm also aware that for many people, having one adult not engaged in waged labour is either impossible or too much of a struggle. We as a family may have little money on a single income, but we are privileged enough to be able to make it happen).

But as the camp demonstrated to me, the kids and adults were loving the unschooling approach. 'Free' is the word that springs to mind—not in the hippy-happy-joy-joy sense, but in terms of autonomy, independence, self-determined.

Around 200 people from across Te Ika-a-Māui/the North Island came and went over the course of the camp, which included co-operative dinners, the odd activity, and lots of play—in the bush, in the sand, at night, in the hall, at the chess table, in the tents, cabins and grass. Lots of noise and lots of fun! And it meant some well-needed downtime for parents.

A market and child-led concert showed that unschooled kids are social, confident and talented (this is obviously something I needed assurance on, as the question I inevitably get asked is how social unschooled children are). Poetry, performance, guitar, dance, jokes — it really was inspiring to see children free to be themselves; to create, to sing and to collaborate.

I was amazed at the huge amount of respect the children had for each other, and the respect adults had for children as people. From teens to toddlers, their interactions were based in a way of being grounded in reciprocity and respect.

Linked to this was the fact that the camp was a co-creation space, which meant that it was organised and run collectively (while allowing space for those who couldn't or didn't want to participate). As the website notes, 'this encourages trust, openness, flexibility, ease and self-responsibility.' Which is apt, considering what I'm reading at the moment:

Commoning is primary to human life. Scholars used to write of “primitive communism.” “The primary commons” renders the experience more clearly. Scarcely a society has existed on the face of the earth which has not had at its heart the commons; the commodity with its individualism and privatization was strictly confined to the margins of the community where severe regulations punished violators...

Capital derides commoning by ideological uses of philosophy, logic, and economics which say the commons is impossible or tragic. The figures of speech in these arguments depend on fantasies of destruction—the desert, the life-boat, the prison. They always assume as axiomatic that concept expressive of capital’s bid for eternity, the ahistorical “Human Nature.”Of course it's far-fetched to claim that this camp was perfectly pre-figuring some kind of post-capitalist society. It was not without its faults and complexities (I would have liked a little more acknowledgment of the tangata whenua of that place, and/or pōwhiri). But as a first-time attendee with much to learn, I've come away feeling inspired, and with a connection to others who have similar values and approaches to education. Bring on the autumn camp!

Many thanks to the behind-the-scenes organisers, the parents who made us feel welcome, and of course, the kids.

Thursday, February 11, 2016

Matike Mai Aotearoa: Independent Working Group on Constitutional Transformation - report released

The Report of Matike Mai Aotearoa: Independent Working Group on Constitutional Transformation has just been released. Convened by Moana Jackson and chaired by Margaret Mutu, extensive consultation across the country was undertaken between 2012-2015 and included 252 hui, written submissions, organised focus groups and one-to-one interviews.

The Terms of Reference sought advice on types of constitutionalism that is based upon He Whakaputanga and Te Tiriti.

“To develop and implement a model for an inclusive Constitution for Aotearoa based on tikanga and kawa, He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Niu Tireni of 1835, Te Tiriti o Waitangi of 1840, and other indigenous human rights instruments which enjoy a wide degree of international recognition”. The Terms of Reference did not ask the Working Group to consider such questions as “How might the Treaty fit within the current Westminster constitutional system” but rather required it to seek advice on a different type of constitutionalism that is based upon He Whakaputanga and Te Tiriti. For that reason this Report uses the term “constitutional transformation” rather than “constitutional change.”It really is an amazing document, both for its simple language and what it could mean for future indigenous-settler/Māori-Pākehā relations.

Read it here: http://www.converge.org.nz/pma/MatikeMaiAotearoaReport.pdf

Monday, February 1, 2016

Sewing Freedom: Philip Josephs, Transnationalism & Early New Zealand Anarchism

Sewing Freedom: Philip Josephs, Transnationalism & Early New Zealand Anarchism is the first

in-depth study of anarchism in New Zealand during the turbulent years of

the early 20th century—a time of wildcat strikes, industrial warfare

and a radical working class counter-culture. Interweaving biography,

cultural history and an array of archival sources, this engaging account

unravels the anarchist-cum-bomber stereotype by piecing together the

life of Philip Josephs—a Latvian-born Jewish tailor, anti-militarist and

founder of the Wellington Freedom Group. Anarchists like Josephs not

only existed in the ‘Workingman’s Paradise’ that was New Zealand, but

were a lively part of its labour movement and the class struggle that

swept through the country, imparting uncredited influence and ideas. Sewing Freedom

places this neglected movement within the global anarchist upsurge, and

unearths the colourful activities of New Zealand’s most radical

advocates for social and economic change.

Shortlisted: Bert Roth Award for Labour History Labour History Project (Sep 2014)

Shortlisted: Best Non-Illustrated Book PANZ Book Design Awards (June 2014)

Shortlisted: Bert Roth Award for Labour History Labour History Project (Sep 2014)

Shortlisted: Best Non-Illustrated Book PANZ Book Design Awards (June 2014)

Review by David Grant in New Zealand Books Quarterly Review (Winter 2014)

Review by Cybele Locke in Australian Historical Studies 45 (2014)

Review by Cam Walker on Scoop (Sep 2013)

‘Denying authority’ – article in Working Life: PSA Journal, p.30 (September 2013)

‘Anarchy stitched into Wellington’s streets’ – article in the Dominion Post (July 2013)

‘Anarchist history wins praise’ – article in the Hutt News (June 2013)

Radio interview with Jared Davidson on 95bfm (June 2013)

Review by Dougal McNeill on the ISO blog (May 2013)

Review on the korynmalius blog (May 2013)

Review by Chris Brickell, Associate Professor of Gender Studies, Otago University on the AK Press tumblr (April 2013)

Video of the Wellington launch On 15 May 2013, Sewing Freedom was launched in Wellington, New Zealand. Held at the Museum of Wellington City & Sea, the launch featured talks by Mark Derby, Barry Pateman, and Jared Davidson. This is a film of those speeches, delivered to around 65 people in the historic Boardroom (38 min.)

MP3 sound recording of the Wellington launch. (38 min.)

Philip Josephs and anarchism in New Zealand by Jared Davidson in Bulletin of the Kate Sharpley Library (July 2012)

Philip Josephs – early anarchist in New Zealand by Jared Davidson in Kosher Koala (May 2012)

Shortlisted: Best Non-Illustrated Book PANZ Book Design Awards (June 2014)

Published by AK Press, Oakland (April, 2013). Includes illustrations by Alec Icky Dunn (Justseeds) and a foreword by Barry Pateman (Kate Sharpley Library, Emma Goldman Papers).

Endorsments

“A ground breaking tale of a rebel life, skillfully unearthed by Davidson. A must read.” - Lucien van der Walt, co-author of Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism

“Filling a much-needed gap, Sewing Freedom deserves a treasured place within the pantheon of serious studies of the origins of the far left in New Zealand.” - David Grant, New Zealand Books Quarterly Review

“Jared Davidson has produced much more than a soundly researched and

very engaging biography of ‘the most prominent anarchist in New

Zealand’. This is an excellent, wide-ranging contribution to our

knowledge of the international (and indeed transnational) anarchist

movement, and sweeps us along in a fascinating story that takes us from

the pogroms in Russian Latvia, to the working-class slums of Victorian

Glasgow, to the early struggles of the nascent labour movement in New

Zealand.” - Dr David Berry, author of The History of the French Anarchist Movement

“This is a fine book that sheds another clear beam of light on the

complex puzzle that is anarchist history. Meticulously researched,

sometimes following barely perceivable trails, thoughtful and incisive,

it presents us with an, as yet, uncharted anarchist history in a

controlled and engaging way. Like all good history it leaves us with

much to think about; and like all good anarchist history it encourages

us to consider how we read, interrogate, and assess the long and,

sometimes, confusing journey towards anarchy.” - Barry Pateman, Kate Sharpley Library archivist & Associate Editor of The Emma Goldman Papers

“Many millions of words have been written on New Zealand history. The

labour movement does not feature prominently in this vast corpus; in

fact, quite the contrary. And within this relatively sparse coverage,

anarchism is almost invariably assigned at best a passing mention. We

must be grateful for Davidson’s determination to restore an anarchist

voice to the history of the outermost reach of the British Empire. In

piecing together the life and beliefs of Philip Josephs, often from the

most fragmentary of surviving evidence, Davidson helps us situate

anarchist beliefs and activities within broader international socialist

currents. By focusing on a significant individual and his tireless

advocacy in several countries, he indicates how such belief systems

transcended national boundaries, not only in the restless lives of

theoreticians and practitioners, but also –and most important of all –in

their universalist message.” - Dr Richard Hill, Professor of New Zealand Studies at Victoria University of Wellington & author of Iron Hand in the Velvet Glove: The Modernisation of Policing in New Zealand 1886-1917

“Jared Davidson has written a ripping narrative, extensively and

thoroughly researched, with a flair and flavour that takes the reader

into the backrooms of the radical movements of anarchism in its early

days in New Zealand. I am delighted with this work of history which

involved my own grandfather so closely.” - Dr Caroline Josephs, artist/writer/storyteller and granddaughter of Philip Josephs, Sydney

“Sewing Freedom works on several levels. It is a meticulous

biography, a portrait of an era, a sophisticated discussion of anarchist

philosophy and activism, and an evocation of radical lives and ideas in

their context. Davidson has designed a fresh, crisp book with visual

impact, nicely enhanced by Alec Icky Dunn’s wonderful sketches of key

places in this history: working class backyards, a miner’s hall and

striking workers under attack by the forces of the state. This

beautifully-executed book tells an important story in New Zealand’s

political history.” - Chris Brickell, Associate Professor of Gender Studies at Otago University and author of Mates and Lovers

Media & Awards

Review by Lucien van der Walt in Anarchist Studies 22 (December 2014)Shortlisted: Bert Roth Award for Labour History Labour History Project (Sep 2014)

Shortlisted: Best Non-Illustrated Book PANZ Book Design Awards (June 2014)

Review by David Grant in New Zealand Books Quarterly Review (Winter 2014)

Review by Cybele Locke in Australian Historical Studies 45 (2014)

Review by Cam Walker on Scoop (Sep 2013)

‘Denying authority’ – article in Working Life: PSA Journal, p.30 (September 2013)

‘Anarchy stitched into Wellington’s streets’ – article in the Dominion Post (July 2013)

‘Anarchist history wins praise’ – article in the Hutt News (June 2013)

Radio interview with Jared Davidson on 95bfm (June 2013)

Review by Dougal McNeill on the ISO blog (May 2013)

Review on the korynmalius blog (May 2013)

Review by Chris Brickell, Associate Professor of Gender Studies, Otago University on the AK Press tumblr (April 2013)

Video of the Wellington launch On 15 May 2013, Sewing Freedom was launched in Wellington, New Zealand. Held at the Museum of Wellington City & Sea, the launch featured talks by Mark Derby, Barry Pateman, and Jared Davidson. This is a film of those speeches, delivered to around 65 people in the historic Boardroom (38 min.)

MP3 sound recording of the Wellington launch. (38 min.)

Philip Josephs and anarchism in New Zealand by Jared Davidson in Bulletin of the Kate Sharpley Library (July 2012)

Philip Josephs – early anarchist in New Zealand by Jared Davidson in Kosher Koala (May 2012)

Stockists

Ask your local bookshop for Sewing Freedom, or buy it online at AKPress, Amazon, or Book Depository (free shipping). To find your closest Library copy, try WorldCat.Saturday, December 26, 2015

Under the Christmas tree, the beach! This season's communising measures...

Happy Christmas fellow wage-slaves! I'm re-reading this Endnotes #2 text and wanted to share a great segment from it:

"The theory of communisation emerged as a critique of various conceptions of the revolution inherited from both the 2nd and 3rd International Marxism of the workers’ movement, as well as its dissident tendencies and oppositions. The experiences of revolutionary failure in the first half of the 20th century seemed to present as the essential question, whether workers can or should exercise their power through the party and state (Leninism, the Italian Communist Left), or through organisation at the point of production (anarcho-syndicalism, the Dutch-German Communist Left).

On the one hand some would claim that it was the absence of the party — or of the right kind of party — that had led to revolutionary chances being missed in Germany, Italy or Spain, while on the other hand others could say that it was precisely the party, and the “statist,” “political” conception of the revolution, that had failed in Russia and played a negative role elsewhere.

Those who developed the theory of communisation rejected this posing of revolution in terms of forms of organisation, and instead aimed to grasp the revolution in terms of its content.

Communisation implied a rejection of the view of revolution as an event where workers take power followed by a period of transition: instead it was to be seen as a movement characterised by immediate communist measures (such as the free distribution of goods) both for their own merit, and as a way of destroying the material basis of the counter-revolution.

If, after a revolution, the bourgeoisie is expropriated but workers remain workers, producing in separate enterprises, dependent on their relation to that workplace for their subsistence, and exchanging with other enterprises, then whether that exchange is self-organised by the workers or given central direction by a “workers’ state” means very little: the capitalist content remains, and sooner or later the distinct role or function of the capitalist will reassert itself.

By contrast, the revolution as a communising movement would destroy — by ceasing to constitute and reproduce them — all capitalist categories: exchange, money, commodities, the existence of separate enterprises, the state and — most fundamentally — wage labour and the working class itself."

So what the hell are 'communist measures'? There's a text on communist measures here, but one Libcom posters note that:

'communisation is a movement at the level of the totality'. So it's not a question of particular acts being communising, and enough of them adding up to communism/revolution, but that acts take on a communising character depending on the movement of which they're a part. This is all a bit abstract, so I'll give an example.

Let's imagine a single factory closes down, and is occupied, taken over and self-managed by its workers. This may or may not be a good thing; I doubt many communisation theorists, even those most critical of self-management would begrudge workers trying to survive, though some argue occupying to demand a higher severance package would be a better approach than assuming management of a failing firm. But a single act like this doesn't challenge the totality of capitalist relations, it would just swap a vertically managed firm for a horizontally managed one, leaving the 'totality' unchanged.

However, if factory takeovers were happening on a mass scale, such that they could start doing away with commercial/commodity relations between them; and at the same time there were insurgent street movements toppling governments; mass refusals to pay rent/mortgages and militant defence of subsequent 'squatting'; collective kitchens springing up to feed insurgents (whether they're 'workers' in a narrow sense, or homeless, or domestic workers, or unemployed or whatever); and free health clinics being opened either by laid off doctors/nurses, or in their spare time, or in occupied hospitals and other buildings... If this was happening across several countries then we might be looking at a communising movement at the level of the totality; toppling state power, superseding commercial relations, making possible social reproduction (housing, food, health) without mediation by money, self-management of the activities necessary for this etc (rather than self-management of commodity production and wage labour).

All a long way to say that: a) things can't go on the way they are, and b) the struggle against the way things are can't necessarily be the same as struggles of the past.

Time for some more reading!

Thursday, October 29, 2015

I designed a poster...

It's been a while, but here's my latest poster for the Labour History Project. It's a play on Lenin's famous text, the red flag, etc etc.

If you're in Wellington make sure to get to this event and help support the work of the LHP: http://www.lhp.org.nz/?p=1208

Tuesday, September 1, 2015

Upcoming AK Press fundraiser in Wellington - 26 September

A fundraising celebration of radical and independent publishing in Aotearoa New Zealand and beyond!

AK Press is a worker-run, collectively managed anarchist publishing and distribution company, in operation since 1990. On March 21st of this year, a fire in a building behind AK’s caught fire and the fire spread to AK’s warehouse. Two people living in the building died in the fire, much of AK’s inventory was damaged by water and smoke, and the city has deemed their building uninhabitable. While they have suffered a major blow they are carrying on and continue to publish and distribute anarchist and radical literature around the world, including to Aotearoa New Zealand. But they need all the help they can get and all money raised at this event will go directly to their fire relief fund.

More information about AK Press and the fire can be found at http://www.akpress.org/fire-relief.html

Speakers so far:

Jared Davidson

Mark Darby

Rebel Press

The Freedom Shop

Kassie Hartendorp

Faith Wilson

Leilani A Visesio

Kerry Ann Lee

Maria McMillan

Pip Adam

Scott Kendrick

Don Franks

Ken Simpson

Barry Pateman

Murdoch Stephens

With music by:

Mr Sterile Assembly

Te Kupu

Gold Medal Famous

The All Seeing Hand

When: Saturday September 26, 2015

Where: Moon, 167 Riddiford St, Newtown, Wellington

$10 to $10 million depending on how generous you're feeling!

Readings from 6:30 pm, music from 9pm

AK Press books will be available for sale through The Freedom Shop.

Sunday, August 23, 2015

Lines of Work: Stories of Jobs and Resistance (review)

Lines of Work: Stories of Jobs and Resistance

By Scott Nikolas Nappalos, ed. (Alberta, Canada: Black Cat Press, 2013)

Review by Jared Davidson, first published in LHP Bulletin 64.

Lines of Work is a fascinating, at times bleak and emotive volume of stories about work and its effect on our lives. How fitting then, that my review copy was waiting for me after my usual 20-minute trip home from work had stretched to four hours, thanks to the flooding in Wellington of 14 May 2015. Work (with a little help from the weather) had kept me away from my loved ones even more than it already does on a day-to-day basis. That period after clocking out was clearly not my own time, but that of capital.

The thirty-two stories in Lines Of Work explore similar examples of contemporary working life. It brings together texts originally published on “Recomposition”, an online publication run by a collective of worker radicals based in the US and Canada. Written between 2009 and 2011, we hear from a range of people in various jobs, including non-profit organisations (which are no different from the rest). The writers are not professionals, and rightly so—the purpose of Lines of Work stems from a desire to link and explore the everyday experiences of people who work as an organising tool. As we know, “the personal is political”, and Lines of Work is an example of a radical praxis that supports the power of discourse without drifting into a Foucauldian abyss.

“In the eyes of dominant culture and the opinions of political culture” writes editor Scott Nappalos in the Introduction, “stories play second fiddle. In political life, literature is at best an emotional tool for theory, something to motivate people around a cause or worse, simply pure entertainment.” Yet “looking at stories in that way is out of step with working life. The lives of working-class people are filled with stories people share every day about their struggles, perspectives, and aspirations” (p.1).

With this in mind, Lines of Work asks us to take a serious look at the way stories can help us build a better society. “There is something powerful in the process of someone who participates in struggle finding a voice to their experiences… reframing the role of stories requires us seeing this process as both part of being an active participant in social struggles, and as a way to participate” (p.2). In doing so a transformation can occur, opening “up space for deeper work” (p.2). Stories about work should be seen “not only for their beauty, tragedy, and motivating power in our lives, but also as a reflection of workers grappling with their world and creating new currents of counter-power autonomous from the dominance of capital and the State” (p.7). Stories of work, therefore, are a “part of workers’ activity to understand and change their lot under capitalism… through storytelling, [the stories] draw out the lessons of workplace woes, offering new paths and perspectives for social change and a new world” (blurb).

As another reviewer has pointed out, “a good amount of these jobs—finance, food service, clerical work, manufacturing bullets for imperialist wars—are not the seeds of a future society but a blight on the present one. There is no straight line from these jobs to a libertarian communist society, nor are most of them (except for the bullet factory, really), strategic ‘choke points’ of capital, as the present theories of circulation dictates that we seek out. A revolutionary struggle would be waged to eliminate these jobs, not to make them cooperative”. Yet this is not necesarily the point of the book. While it may lack the “what next” element some readers crave, Lines of Work is a welcome addition to the subjective aspect of working-class experience that is often missing from theoretical accounts of struggle.

In Lines of Work, the stories are organised into three sections: resistance, time, and sleep. The theme of “resistance” “gives accounts of trying to correct problems at work, and collective lessons that came out of those struggles” (p.7). What struck me about this section was the arbitrariness that so many workers have to deal with in their day-to-day work, from not being allowed to celebrate birthdays to managerial changes to a roster. These are not tales of general strikes or historic moments, but stories of little struggles: of the mundane yet important tasks that can either foster resistance or keep a workforce down. Some victories are shared, but so are many losses and regrets at what happened, or what could have been done differently.

“Time” was my favourite section and the largest in the book. It covers “the world of work, in all that it demands and takes from us” (p.7). What this means is spelled out in rare, intimate detail, and in a way that instantly resonates (well, for me at least). Travel to and from work, repetitive on-the-job tasks, shitty customers, shitty bosses, sexism and difficult workplace conversations, racism, identity, class, job control, poor health, despair—are explored across workplaces totally different yet unsurprisingly the same. I light-heartedly explained this to a friend as “the commonalities of crappiness”. But in all seriousness, what is great about this book is how the stories connect the common elements of working life, and place our own experiences of work into an international context.

The section titled “Sleep and Dreams” shares examples of how capital invades what is supposedly our “own” time: our sleep. Who hasn’t dreamed about work? Had a nightmare of turning up to work a job they quit years ago? “Awaking from a work dream only to find one’s work day only beginning is perhaps one of the banal horrors shared most widely by the entire worldwide proletariat”. These stories of dreams and (lack of) sleep are sad yet fascinating in their own right. But the underlining idea of un-free time and the reproduction of capital (in the form of what we do in between clocking out and signing in) is a strong critique of work as a separate activity of life—of alienation. It is the perfect way to end an engaging and highly readable expose of contemporary working life, and how unnatural the wage relation truly is.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)