Wednesday, January 28, 2015

On the miseries of political life

This is my response to a text written on the AWSM blog: http://www.awsm.nz/2014/10/30/the-miseries-of-political-life/.

Thursday, January 1, 2015

What is anarchism? - in one sentence

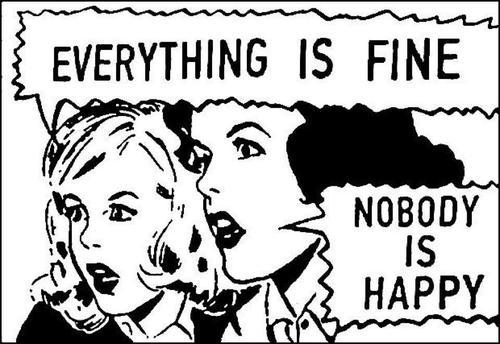

| Josh MacPhee, Revolution of Everyday Life, postcard |

While I shed my evangelical fervor a long time ago, I still want to be able to talk with those around me about what drives my thoughts and actions.

Related to this is one of my goals for 2015: to speak and write in plain English. So I thought I would share what usually I say when I am asked what anarchism is.

Anarchists believe that no one should have the power to coerce or exploit another, that we could enjoy a life without capitalism, without government, and be free to decide how to live and work with those around us.

This is a huge simplification of a rich and complex movement, and leaves a lot out. But I find it is a nice conversation starter. I have used other terms at other times, such as 'wage labour' for 'capitalism', 'the state' for 'government', or 'organise' for 'decide'. However these are slightly more abstract or harder to relate to. Plus 'wage labour' does not cover all of what capitalism does to our relationships, our environment, and our lives.

You can find out more about anarchism on this blog, and online. For example, Libcom.org has these great guides on what anarchists are against, and what we would like to see instead: http://libcom.org/library/libcom-introductory-guide

Happy New Year!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Despite agreeing with much of the text, I guess what jarred me was the feeling that it was too black and white, and I couldn’t tell if the Situationist quotes were for real or satire. I think what Olly says about certain types of work leading to further investment in ‘the system’ is spot on. To be aware of the contradictions in our work, and to know how our work reproduces capital, is the first step in challenging and ending that work.

But if I understand what this text suggests, it is that we should aim our struggle towards particular jobs. Olly points out the flaws of this approach, yet it still reads as if certain jobs have more potential for class struggle over others.

I feel this is problematic. It makes me think of those who argue that Auckland should be the main place of struggle, because that’s where the biggest employers are. Or that the online financial sector should be the place of struggle, because that is where the finance sector operates.

Playing havoc with the economy or the financial sector might bring down the economy or the financial sector, but this is not the same as ending capitalism. As we know, capital is not a place, but a social relationship. Thinking about where this relationship might best be ruptured is useful, but trying to pinpoint exact locations of struggle is extremely difficult and possibly a distraction from a broader, collective approach.

Yet it is clear that certain work changes the way we relate to others, as Olly points out. This division of labour, or the divisions between ourselves, is super important – even more so now that many people do not identify as workers, or as a class (this might not be such a bad thing, depending on your point of view, but that is another discussion altogether).

However most people can relate to discussions about work; to the day-to-day content and activity of their jobs (waged or unwaged). I think this is a potentially fruitful way forward for those of us who wish to end the wage relation. Rather than spending time raising the ‘class consciousness’ of our peers in an abstract sense, we can get to the heart of our work, and how we reproduce capital.

Feminist and marxist, Iris Young, talks about how the division of labour may be a more useful way forward than that of class. In ‘The Unhappy Marriage’ she writes that “the division of labour operates as a category broader and more fundamental than class. Division of labour, moreover, accounts for specific cleavages and contradictions within a class… [it] can not only refer to a set of phenomena broader than that of class, but also more concrete. It refers specifically to the activity of labour itself, and the specific social and institutional relations of that activity.” She goes on to talk about how this might speak to the role of professionals – ie the subject of Olly’s text.

I find this approach helpful, because it makes clear that all work reproduces the wage relation – whether you’re an academic, information worker, or a kitchen hand – and that struggle around the activity of work is potentially more fruitful than trying to pinpoint which jobs are best to spend energy on.

In other words, what might be more constructive is to discuss the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of struggle against the wage relation, wherever that struggle may be, rather than focusing on ‘where’.

This relates to another aspect of this text I find troublesome. It feels like another anarchist text policing individuals within the movement for their decisions. It seems to place a lot of emphasis on the role of the individual anarchist. I get this, because that is what we can relate to in our own lives and our own organising, as anarchists. But this does not strike me as a way forward, but a further step inward.

Olly clarifies that we need a collective response to this on Redline, which is cool to hear.

Finally, I don’t agree with the ‘poverty of everyday life’ comment of Olly’s. Struggle around our everyday life is a must, but poverty often begets more poverty, and not struggle. I don’t like what this leads to (even if it is unintentional) – that the worse off people’s jobs are, the more they will struggle against it. If anything, history has shown that struggle on a collective scale tends to take place when things are good or improving for workers (a huge generalisation, I know).

I’m not sure if what I’m trying to say makes sense. I guess the short of it is that the potential for mass, collective struggle against the wage relation (and work) is all around us. We don’t need to narrow that to a particular type of work, especially when there may be important sites of struggle that is neglected in doing so. For example, could capital reproduce itself without childcare and daycare centres? I’m not saying this is a great example, but it is the type of question I’d love to discuss, rather than trying to monitor the further personification of capital by individual comrades.