Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History was published by Haitian writer and anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot in 1995. As I’ve written elsewhere, Silencing the Past profoundly shaped the way I understand archives and the production of history. It is a go-to text for writers, educators and students across the globe and continues to offer insights into why some stories are remembered and others are not, and how historical narratives are produced and reproduced.

In Silencing the Past, Trouillot

is less interested in what history is, but how history works. He writes, ‘This

book is about history and power. It deals with the many ways in which the

production of historical narratives involves the uneven contribution of

competing groups and individuals who have unequal access to the means for such

production. The forces I will expose are less visible than gunfire, class

property or political crusades. I want to argue that they are no less

powerful.’

Trouillot begins chapter one with the

example of the Alamo, which was won by Santa Anna in March 1836 but ‘lost’ in

the longer narrative. A few weeks after the Mexican victory at the Alamo, Santa

Anna was captured by the Americans at San Jacinto. The American victory was

punctuated with shouts of ‘Remember the Alamo’. With their battle cry and its reference

to Alamo, writes Trouillot, the men under Sam Houston doubly made history: ‘as

actors, they captured Santa Anna… as narrators, they gave the Alamo story a new

meaning.’ They reversed for more than a century the victory Santa Anna thought

he had gained at the Alamo.

This is Trouillot’s way of introducing a

key tenet of the book: the double meaning of the word ‘history’. The double

meaning (or the double-sided historicity) he is interested in is history as

what happened and history as that which is said to have

happened. The first places emphasis on the sociohistorical process, while the

second places emphasis on our knowledge of that process or the story about that

process. As Trouillot demonstrates, neither are as straight forward as they

seem.

From the Alamo through to the Haitian

Revolution and the ‘discovery’ of the Americas by Columbus, Trouillot examines the

blurriness of this double meaning, tracking power and the production of history

through multiple examples, especially their silences.

First, Trouillot offers a critique of the

storage model of history, in which history is understood as the simple recall

of important past experiences and events. In this model, history is to a

collective what remembrance is to an individual, ‘the more or less conscious

retrieval of past experiences stored in memory.’

Trouillot points out the flaws in this

model, using the example of a person recalling in monologue form all their

memories of a particular event, or even their life. ‘Consider a monologue

describing in sequence all of an individual’s recollections. It would sound as

a meaningless cacophony even to the narrator.’ And what about the events that

shape us, but which we may not be able to remember or recall. The idea that the

past is fixed and separate and can be accurately recalled at will is not only

cognitively impossible, it does not form a history. As Trouillot notes, ‘the

past does not exist independently from the present. Indeed, the past is only

past because there is a present.’ In this sense, ‘the past has no content. The

past – or more accurately, pastness – is a position.’

The problem of determining what belongs

to the past is even harder when that past is said to be shared. When does the

life of a collective start? How does a collective decide which events to

recall, to include or exclude? ‘The storage model’ writes Trouillot, ‘assumes

not only the past to be remembered but the collective subject that does the

remembering.’ Who are the ‘we’ in this example?

Trouillot comes back to the double

meaning of the word history and how the search for what history is has led

people to either a) demarcate precisely and at all times the dividing line

between historical process (what happened) and historical knowledge (that

which is said to have happened), or b) to conflate them completely. Instead,

Trioullot suggests that between the two extremes of a mechanically “realist” or

positivist approach, or the naïve “constructivist” or relativist approach,

there is a middle approach – one that asks how history works rather than what

history is. ‘For what history is changes with time and place or, better said,

history reveals itself through the production of specific narratives. What

matters most are the processes and conditions of production of such narratives.

Only a focus on that process can uncover the ways in which the two sides of historicity

intertwine in a particular context. Only through that overlap can we discover

the differential exercise of power that makes some narratives possible and

silences others.’

Silences

Trouillot’s treatment of silences in the

production of history are especially important. Rather than mere absences or

presences – which are too passive for Trouillot – silence is ‘an active and

transitive process: one “silences” a fact or an individual as a silencer

silences a gun. One engages in the practice of silencing. Mentions and silences

are thus active.’ Trouillot emphasises that history is constantly produced,

that what we understand as ‘history’ changes with time and place, and that what

is said to have happened as the recall of facts is indeed a process filled with

silences. For Trouillot, it is not just a matter of what is remembered or

forgotten. Silences are produced and reproduced throughout any telling of a story.

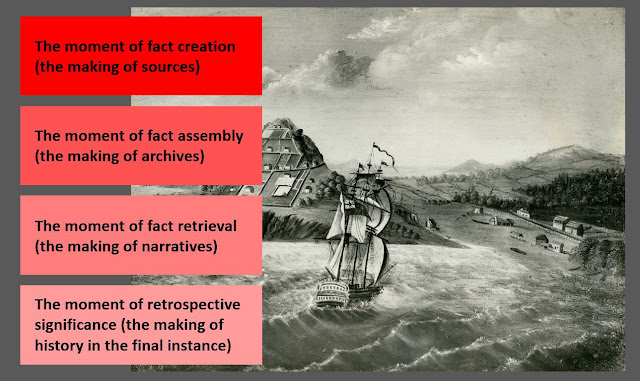

In one of the most important and oft-cited

passages of the book, Trouillot writes that ‘silences enter the process of

historical production at four crucial moments: the moment of fact creation (the

making of sources); the moment of fact assembly (the making of archives); the

moment of fact retrieval (the making of narratives); and the moment of

retrospective significance (the making of history in the final instance).’

We will come back to these soon. But for

now, he writes that these moments ‘are not meant to provide a realistic

description of the making of any individual narrative. Rather, they help us

understand why not all silences are equal and why they cannot be addressed – or

redressed – in the same manner.’ In other words, ‘any historical narrative is a

particular bundle of silences, the result of a unique process, and the

operation required to deconstruct these silences will vary accordingly.’

Hence the mention of power in the by-line

of Silencing the Past. For Trioullot, power ‘does not enter the story

once and for all, but at different times and from different angles. It precedes

the narrative proper, contributes to its creation and to its interpretation.’

‘Power is constitutive of the story’ writes Trouillot. ‘Tracking power through

various moments helps emphasise the fundamentally processual character of

historical production, to insist that what history is matters less that how

history works.’

Archives 101 (or the moment fact assembly, the making of archives)

This is where an understanding of context

is so important, and why provenance and original order are keystones to

archival practice. It is context that allows us to make sense of a source and

its creation, and to place it in relation to others. And context helps us to think

about the four moments that silence can enter the historical process.

Like the word history, the word archive

has a double meaning. There are archives as evidence, and archives as an

institution or repository. Both have power to marshal narratives and make

meanings. And stories are key to both.

At their most basic, archives

are stories. Whether we’re talking about archives as evidence or archival

institutions, all peoples use archives as stories, whether transmitted through

speech, written in text, woven within tāniko patterns or embodied in tā moko,

performed as ritual or shared in everyday practices, or displayed in objects or

in the land itself. For Trouillot, ‘archives are the institutions that organise

facts and sources and condition the possibility of existence of historical

statements.’ These ‘historical narratives are premised on previous

understandings, which are themselves premised on the distribution of archival

power’. As Rodney Carter writes,

‘Archival power is, in part, the power to allow voices to be

heard. It consists of highlighting certain narratives and of including certain

types of records created by certain groups. The power of the archive is

witnessed in the act of inclusion, but this is only one of its components. The

power to exclude is a fundamental aspect of the archive. Inevitably, there are

distortions, omissions, erasures, and silences in the archive. Not every story

is told.’

Yet throughout the twentieth century,

public archives were seen as passive, objective and neutral. The public

archivist was an impartial custodian – interpretation was the job of those

using archives and not that of the archivist. ‘The good Archivist’, wrote Sir

Hilary Jenkinson, the grandfather of the Western archival canon, was ‘perhaps

the most selfless devotee of Truth the modern world produces.’ Archives were

the evidence from which Truth (with a capital ‘T’) could be found.

More recently, the post-custodial turn

has challenged this view. A questioning of the profession’s objectivity has

reframed or refigured archives and archival institutions. Archives are

increasingly viewed as social constructs – they don’t simply ‘arrive or emerge

fully formed, nor are they innocent of struggles for power in either their

creation or their interpretive applications . . . all archives come into being

in and as history as a result of specific political, cultural, and

socioeconomic pressures.’ And for Trouillot, this is also true of the moment of

fact creation – the making of sources, or archives as evidence.

Facts and Historical Facts (or the moment of fact creation and the moment of fact retrieval)

Following Trouillot and others, the

evidential nature of archives as sources have been questioned: no longer can we

think of sources as the simple bearers of fact or truth. Just as much as oral

testimony, a written document reflects the biases and needs of its creator. It

seems obvious, but it is important to note that sources are not neutral or

natural but are created. And as Trouilott writes, ‘facts are not created equal:

the production of traces is always also the creation of silences.’

‘Silences are inherent in history’ argues

Trouillot ‘because any single event enters history with some of its

constituting parts missing. Something is always left out while something else

is recorded.’ The ‘facts’ people choose to record come with their own ‘inborn

absences, specific to its production.’ Indeed, silences are necessary to any

account, otherwise that account would be unintelligible.

Think back to the storage-model example.

A similar process happens at the moment of fact creation, the making of

sources. Trouillot uses the example of a sportscaster or commentator calling a

game. If the commentator ‘told us every “thing” that happened at each and every

moment, we would not understand anything.’ Things are left out. Some facts are

ignored while others are highlighted. Silences are inherent (and necessary) at

the moment of fact creation.

It's useful here to clarify that

Trouillot is not arguing there are no such things as facts. Following Trouillot

and others, Kevin

Gannon gives the following example of how the moment of fact retrieval (the

making of narratives) is an active process:

There are facts, and there are historical facts. Fact: lots

of people crossed the Rubicon. Historical fact: Julius Caesar crossed the

Rubicon in 49 BCE. A fact is embedded within a historical context that gives it

historical significance and meaning. So when does a plain old “fact” rise to

the level of “historical fact?” The short answer: when a historian decides it

does. The fact and its context acquire historical meaning in retrospect, as

they are recovered, interpreted, and presented by the historian.

In other words, ‘significance is not

inherent, but bestowed’. For Gannon, ‘the myth of objectivity presupposes

inherent significance’. Yet defining what fact is ‘important’ or ‘significant’

is contested, is wrapped up in cultural and political meanings, is shaped by relations

of power that are themselves historical, and shifts over time. What is

important to some people is not for others. ‘The assertion of “historical

importance” is really a claim about things that matter, and more tellingly,

things that don’t matter.’

It’s in this way that all writing and

historical research is political. The topics we choose to study and the facts,

stories and people we give significance to is not objective. The facts cannot

speak for themselves, just as a historian cannot simply record the past ‘as it

happened’. As I write in Blood

and Dirt, all historians draw upon methods and practices within their

ideological framework, including (and especially) historians who claim to be disinterested,

even-handed and simply recalling the facts. The writing of history, argued

Douglas Hay, ‘is deeply conditioned not only by our personal political and

moral histories, but also by the times in which we live, and where we live’.

Whether we acknowledge it or not, historians ‘take stands by our choice of

words, handling of evidence, and analytic categories. And also by our

silences.’ Or to echo Trouillot: ‘one engages in the practice of silencing.

Mentions and silences are thus active.’

This brings us all the way back to

archives as stories, history as produced by power, and the importance of

context. And back to Trouillot’s four moments of silencing.

Matthew Conroy and the four moments of silencing

The moment of fact creation (the

making of sources)

Yet in all his letters and journals, Samuel

Marsden leaves Matthew Conroy off the Active’s passenger list for November 1814, despite

Matthew advertising his intention to sail to the Bay of Islands in the Sydney

newspapers and despite Marsden acknowledging the importance of his pair of

sawyers in subsequent letters. What’s more, Samuel Marsden knew Conroy – it was

Marsden who had led investigations into the plot of August 1800.

Writing

to Josiah Pratt on 28 November 1814, Marsden outlines the passengers aboard

the Active and its historic mission:

‘When I wrote the last hasty Line I hoped to be near New Zealand before this time— we have been lying at the mouth of the Harbour detained by contrary winds ever since till, this morning— we are now leaving the Heads of Port Jackson with a fair wind— The number of Souls on Board men women and Children are 34— Europeans, Thomas Hansen Master, and his wife— Messrs Kendall Hall & King and their wives, and five Children John Hunter Carpenter— Alexr Ross mate Henry Shaffery Sailor- Richd Stockwell, Servant to Mr Kendall Thomas Namblton Cook— Wm. Campbell weaver— and Flax dresser— Walter Hall Smith.’

In other letters (later compiled as Marsden's account of the 1814 sailing), the passenger list is different again:

On Monday the 28th we weighed Anchor, and got out to sea, the number of persons on board (including women and children, were thirty-five— Mr Hanson, Master, his wife and son, Messrs Kendall, Hall, and King with their wives and five children;— 8 New Zealanders— two Otaheitans and four Europeans belonging to the vessel, besides Mr Nicholas, myself, two Sawyers, one Smith, and one runaway convict (as we found him to be afterwards)

Here, at least, the presence of two sawyers aboard the Active are mentioned. But why is Matthew Conroy never named in these sources? There are several

possibilities. For one, Marsden hated Irish convicts. Was Conroy’s

transportation as an Irish rebel and his role in the 1800 plot the reason Marsden left his name off the historic passenger list? Marsden names other convicts as

passengers, including the ticket-of-leave seaman Henry Shaffery. Is this an

example of the dialectics of silences Trouillot observes in the story of Sans

Souci, where naming one thing actively silences the other (in other words, by

naming Shaffery the convict seaman, Marsden silences Conroy the Irish rebel)?

Or did he simply forget Matthew Conroy was onboard when he penned this first

list?

The moment of fact assembly (the

making of archives)

As a convict, Matthew Conroy did not

leave his own account of his passage in the form of manuscripts or diaries. In

the words of Trouillot, he was an actor but not a narrator. His convict status

and working life contributed to the inequalities of his historical narrative at

the source. The content of the traditional archive, shaped as they are by power

and the preservation of certain voices over others, cemented this fact. Yet he

is present in other archives such as newspapers (which recorded his presence

aboard the Active on the November 1814 sailing). And reading Marsden’s own archive for silences

reveals Conroy’s presence too.

Upon his return to Sydney, Marsden wrote that: ‘The following number of persons were left at Runghee Hoo

[sic]. Mr & Mrs Kendall 1 Servant and 3 boys – Mr and Mrs Hall and 1 Boy –

Mr and Mrs King & 2 Boys These belonging to the Society. One pair of

Sawyers and a Black Smith bound for a time’ [my emphasis]. The pair of

sawyers were William Campbell and Matthew Conroy, who were some of the first people ashore when the Active arrived. In the same letter Marsden writes:

‘I have since sent over the Wives of the Smith, and one Sawyer (the other being

a single Man) and 2 Children.’ These are Eleanor Hall, wife of the blacksmith

Walter Hall, and Ann Kelly, wife of Matthew Conroy. Both are listed as

intending to sail on the Active in April 1815 to join their husbands, who were already in New Zealand, having sailed on the Active in November 1814. Campbell, Conroy and their families would soon move to Waitangi, where they built the first ever European structures on the site.

The mention of sawyers in Marsden’s later

correspondence does not make it through to the various online archives that

list the Active’s passengers. Entries on genealogical websites such as WikiTree

and Yesteryears reproduce the lists and sources without Matthew Conroy present. In doing so, these online

archives reproduce the original moment of silencing and shape the

narratives that will make use of them.

The moment of fact retrieval (the

making of narratives)

Nearly every account since has continued

this silence which, for such a pivotal event in New Zealand’s history – a Mayflower-

esque, birth- of-the- nation moment for some – is telling. It was continued at

the time by a fellow passenger and friend of Marsden, John Liddiard Nicholas, in

his Narrative

of a Voyage to New Zealand: Performed in the Years 1814 and 1815 in Company

with the Rev. Samuel Marsden (Hughes and Baynes, London, 1817). And it

has continued into the present, from Robert McNab and John Rawson Elder to Judith

Binney and Anne Salmond.

Of course, to focus on Matthew Conroy is to silence the presence of the other convicts, Māori rangatira, missionaries,

women, children and crew on board the Active. Instead, my narrative of Hohi centres

Matthew and places him aboard the Active in November 1814 for several

reasons. First, the lists of those said to be aboard the Active and who

arrived to found New Zealand’s first mission are wrong. That which is said to

have happened is incorrect. Second, the fact that Irish convicts like Conroy helped

found New Zealand’s first mission is important to my argument: that convict

labour was not marginal but core to the colonisation of New Zealand. Third, it

connects New Zealand (through Matthew Conroy) to Irish political and social

struggles in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and that’s just plain

interesting!

The moment of retrospective

significance (the making of history in the final instance)

What others will make of my narrative

about the role of prison labour in New Zealand is yet to be determined. I believe

the role of convicts like Matthew Conroy is significant, for it shapes our wider

understanding of the use of convict labour in the making of New Zealand from

the very beginning of Pākehā settlement. From 1814 onwards, the unfree labour

of workers such as Matthew Conroy have contributed to the making of modern New

Zealand in important-yet-overlooked ways. The example of Matthew Conroy speaks

to these moments of silences, to the various makings of sources, archives and narratives

that in turn shape the making of history in the final instance. But as

Trouillot would no doubt remind us, nothing is final in history.

These notes come from a talk I gave for the Kapiti WEA, 19 August 2023. Some of the content is republished from my Overland article on Silencing the Past, as well as my chapter for Public Knowledge. The edition of Silencing the Past I reference is the Beacon Press anniversary edition.