“Power keeps hacking away at the weeds, but it can’t pull out the roots without threatening itself.”

“Power keeps hacking away at the weeds, but it can’t pull out the roots without threatening itself.”— Eduardo Galeano

We live in troubled times. The National Government has set in motion a number of attacks on the working class: prisons open while schools close, there’s been cuts to education and ACC support for victims of sexual abuse, a draconian search and surveillance bill proposed, plans to mine conservation land, GST hikes, and changes to the benefit that would extend the patriarchal hand of the state even more. But let’s not kid ourselves into thinking a Labour Government (or a Green one) would be any better — government, under whatever facade, is still the rule of the few over the many.

Capitalism, hand-in-hand with the state once again finds itself in an economic situation that hits those already feeling the effects of a bankrupt system. In Aotearoa (and across the globe) we are witnessing wage freezes coupled with rising prices. Companies close or move offshore, resulting in workers losing their jobs — our livelihoods are destroyed in their never-ending scramble for profit. We unwillingly pay for a crisis not of our doing.

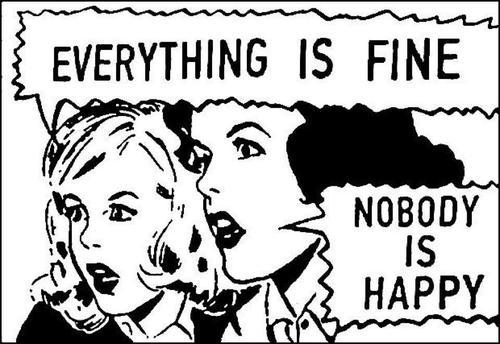

The responses to these attacks have not challenged the state in any meaningful way. Protest activity, while at times large in number has been small in results. Trade unions have failed dismally in resisting the wind back of workers’ gains, completely lacking in both radical ideology and effective activity. Politicians — well they’re part of the problem and will never offer any kind of solution that would threaten their positions of privilege.

Unfortunately, the overwhelming answer for many is to give up their power to that of a representative (politician, community bureaucrat or union official) who will supposedly act on our behalf. We are encouraged to believe that we are powerless to effect any real change in our lives, and political structures are designed to reinforce this. Yet as long as a minority make decisions on our behalf we cannot be free. The sense of community, solidarity, and collective action needed for meaningful change is diffused through structures that privilege a debasing of power (giving our power to somebody else).

Challenging this trend towards the delegation of activity to others is no easy feat, yet it’s one way to move from current defensive action and onto the offensive. Structures and tactics that empower, employ direct action and offer revolutionary alternatives to capitalism and the state are needed more than ever. The time has come for real resistance, for the building of a movement that will effect actual change. This is nothing new. Nor are we the first to point this out. Establishing solidarity and gaining real power through struggle will enable us to break with a culture of dependency and the existing order: this is the pressing task ahead.

“You can’t destroy a society by using the organs which are there to preserve it… any class who wants to liberate itself must create its own organs.”— H. Lagardell

Recent protest action has been merely symbolic and sporadic. We turn up, feel disillusioned, and go home. Politicians then get kudos and claim ‘grassroots’ bragging rights. Nothing changes. There are next to no organisational links being made, analysis of the root causes of the issues we protest against are not being heard, and there’s not much relevant follow-up action. These protests, if they do draw people along, are limited to the usual lobbying of government and illustrate quite plainly the passivity that is symptomatic of a culture of representation.

This same ineffectuality carries through to trade union structures. While there are many sincere and militant members in these unions, a union’s hierarchical and bureaucratic nature limits their scope. It should be clear to all by now that any chance of using the existing unions as tools of social change is, well, kaput — due to their mediating position within capitalism, their conciliatory rather than confrontational stance, and their limitation to trade or workplace.

The last century has been full of failed attempts to reform trade unions. Any reform attempt that seriously threatens the union’s role as ‘social partners’ to management would require a significant upsurge in militancy from the membership. This upsurge would naturally have to come about through actual class struggle, so it seems odd to focus on making an existing union ‘more radical’ when the struggle needed to make it more radical would be enough on its own. This approach equates working class action with trade union action. Yes, lets work with those in unions who share a critique of them and win members to our ideas, but our orientation should be towards actual working class conflict, not one particular form that conflict can take (ie the traditional trade union form). To become absorbed in current unions and their hierarchy destroys militancy and meaningful action.

Furthermore, current unions cause divisions between different groups of workers (non-members/ members of other unions) in the same workplace, trade or industry who share the same interests, acting as a barrier to common class action. A focus on current unions in Aotearoa also neglects their low membership — it also ignores sites of struggle outside of the traditional union’s scope such as unpaid work in the home and community, fights by the unemployed, possible rent strikes etc.

We must take note and move on from the failed forms of the past and look to foster effective struggle — to build dual power and a culture of resistance.

“We carry a new world here, in our hearts. That world is growing this minute.”— Buenaventura Durruti

What do we mean by dual power, and how can we build it? Dual power can be understood as a way of practicing anarchist methods of organisation in order to grow a culture of resistance. It means encouraging direct control of struggle by those in struggle, the practice of non-hierarchical workplace and community assemblies, and collective decision-making based on direct democracy. It’s a way of challenging the power of boss, landlord and government until such time we can abolish them. Building dual power challenges authoritarian structures of power and at the same time, points towards the libertarian future we envision. It not only opposes the state, it also prepares for the difficult confrontations and questions that will arise in a revolutionary situation.

Dual power has to come about through struggle, through ongoing organising around real (not perceived) needs, and through direct action. Running a collective for food distribution or a radical bookshop, while having its own value, does not really confront wider social relations — this is collectively managing a resource, not the building of dual power. Dual power is not prefigurative in the sense that it is building counter institutions that will magically grow within capitalism and replace it once it’s gone. Dual power is prefigurative in terms of the means we use now, the way we organise our struggles, and the way we relate to others during that struggle. Building dual power points to a possible, but not predetermined future.

Dual power can’t be built in isolation or by traditional structures such as trade unions or political parties, as such structures are not set up to encourage such a sharing of power (as we pointed out above). This is where some kind of network that would span across union lines and workplace isolation — and link to the wider community — could play a significant role.

“History always repeats itself: first time as tragedy, second time as farce.”— Karl Marx

Revisiting successful aspects of the anarcho-syndicalist tradition and its tactics of revolutionary struggle (within and outside of the workplace) is something that could potentially move beyond representation and build the culture of resistance described above. By coming together in one network based on direct action, solidarity and the ideas of anarchism, we could offer a very real alternative to both reformist action and the capitalist system itself. It could do what the current unions can’t or won’t do.

We don’t buy the argument that what’s needed is a similar network but without the explicitly anarchist position. Membership is not the goal of a successful network, meaningful struggle with a radical vision is. The focus would be to build class conflict, not the building of a union. To fetishise union membership over radical content has failed time and time again — an effective network should focus on class struggle rather than recruiting as many people as possible. A network of 20 people who manage to foster the growth of radical assemblies wherever they are (workplace or community) would have a larger effect than a network of 200 without any confrontational vision or strategy.

Likewise, a network that waters down its politics to a perceived level of resistance acceptable to people ends up reducing the level of both. This is the problem with ‘pure syndicalism’ that would concentrate on economic demands (wages etc) without an anarchist analysis of political structures that enforce wage slavery. It is absurd to say that someone who could be concerned with the money they receive would not also be concerned with why that money exists and how it is shared around. It’s also absurd to assume people don’t question the fact they have to work for a wage all their life. We need to move beyond pure economics and question the political nature of work itself.

“An organization must always remember that its objective is not getting people to listen to speeches by experts, but getting them to speak for themselves.”— Guy Debord

Instead, the role of those of us in a network would be to put forward explicitly anarchist ideas and call for open assemblies in our workplace or community struggles. We would argue for direct control of these struggles by the mass assembly itself (not by any union or representative, including our own network). This means wherever we are based we should try to get together with our workmates and neighbours to collectively discuss our problems, regardless of whether they are in the network or not. Anyone who is affected by a particular issue should be included and involved, regardless of their union membership, place of employment, gender, race or age. The key is the self-activity of all of those concerned, to widen the fight and encourage a state of permanent dialogue.

By promoting direct action and solidarity, putting across anarchist ideas and offering practical examples of those ideas in practice, we would hopefully start to build a culture of resistance. This is vastly different to the current representative unions or community boards, whose unaccountable officials take it on themselves to control the fight and steer it along an acceptable path. By practicing and promoting mass meetings in times of struggle, we plant the seeds of ongoing, relevant forms of resistance which empower all of those effected — not just network members, but those who aren’t members of the network and who may never want to be.

A network could also offer important solidarity to those who are isolated (such as sub-contractors, temps, causal workers, the unemployed and those at home) and help build a sense of community. It could act as an important source of skill sharing and education — doing all the useful things the current unions do (acting as source of advice, sharing knowledge on labour law, foster solidarity etc) while critiquing their legalist and bureaucratic frameworks. Advice on employment law, community law, bullying at work, health and safety, WINZ and benefit changes — these are all important needs that a network could meet.

However it’s not our job as anarchists to resolve the problems of capitalism, but to keep alive the differences between the exploited and the exploiter, to build a culture of resistance. Our skill sharing and advice must be geared towards this vision. While we should offer practical support we can’t lose sight of our anarchist critique of the current system and our ultimate aim of social revolution: the network is not a help line that simply privileges outsider expertise, but is a fighting organization aimed at empowering those in need and encouraging radical self-activity.

If the activity of such a network related to real needs, was structured so that it involved the wider community in meeting those needs, and illustrated anarchist ideas in practice, it would show that anarchism is relevant to everyday life more effectively than a flyer, discussion group or theoretical journal ever could.

“The self-emancipation of the working class is the breakdown of capitalism”— Anton Pannekoek

Historically we are currently in a low period of radical struggle, partly because of the culture of representation described above. But radical struggle doesn't pick up by magic, by the right mix of historical context. Struggle picks up through struggle, through the self-activity of the working class. The economic breakdown of capitalism doesn’t equate to radical change: just because we’re experiencing an economic downturn doesn’t mean the social revolution is on our doorstep. Nor does capitalism follow a pre-determined tune that allows us to sit back and wait for it to play out. Capitalism has the ability to adapt and even profit from such downturns. As the quote above illustrates (and history proves), the self-activity of those in struggle is paramount to moving beyond a capitalist ‘crisis’ to social revolution. A network and its activity could aid in this upswing of struggle.

A revolutionary network premised on the ideas and tactics described above is what Beyond Resistance aims to help create in the near future. We call for and encourage discussion about these ideas and tactics — if you agree or disagree then let’s get talking. An email list has been set up for this very purpose: discussionbeyondresistance-subscribe (at) lists.riseup.net We hope to start regionally, but we invite all those in Aotearoa interested in such a network and its formation to participate in a hui tentatively organised for September 2010. Any input and knowledge is welcomed. Let us move forward together in the fight against this inhumane, patriarchal and exploitative system and start to build a culture of resistance in Aotearoa. — JUNE 2010.

beyondresistance.wordpress.comExamples and further reading:Solidarity FederationAnarchist Workers NetworkSeattle Solidarity NetworkStrategy and Struggle: anarcho-syndicalism in the 21st centuryAnarcho-syndicalism in Puerto RealTo Work or Not to Work: Is that the Question?Winning the Class War: an anarcho-syndicalist strategy

Despite agreeing with much of the text, I guess what jarred me was the feeling that it was too black and white, and I couldn’t tell if the Situationist quotes were for real or satire. I think what Olly says about certain types of work leading to further investment in ‘the system’ is spot on. To be aware of the contradictions in our work, and to know how our work reproduces capital, is the first step in challenging and ending that work.

But if I understand what this text suggests, it is that we should aim our struggle towards particular jobs. Olly points out the flaws of this approach, yet it still reads as if certain jobs have more potential for class struggle over others.

I feel this is problematic. It makes me think of those who argue that Auckland should be the main place of struggle, because that’s where the biggest employers are. Or that the online financial sector should be the place of struggle, because that is where the finance sector operates.

Playing havoc with the economy or the financial sector might bring down the economy or the financial sector, but this is not the same as ending capitalism. As we know, capital is not a place, but a social relationship. Thinking about where this relationship might best be ruptured is useful, but trying to pinpoint exact locations of struggle is extremely difficult and possibly a distraction from a broader, collective approach.

Yet it is clear that certain work changes the way we relate to others, as Olly points out. This division of labour, or the divisions between ourselves, is super important – even more so now that many people do not identify as workers, or as a class (this might not be such a bad thing, depending on your point of view, but that is another discussion altogether).

However most people can relate to discussions about work; to the day-to-day content and activity of their jobs (waged or unwaged). I think this is a potentially fruitful way forward for those of us who wish to end the wage relation. Rather than spending time raising the ‘class consciousness’ of our peers in an abstract sense, we can get to the heart of our work, and how we reproduce capital.

Feminist and marxist, Iris Young, talks about how the division of labour may be a more useful way forward than that of class. In ‘The Unhappy Marriage’ she writes that “the division of labour operates as a category broader and more fundamental than class. Division of labour, moreover, accounts for specific cleavages and contradictions within a class… [it] can not only refer to a set of phenomena broader than that of class, but also more concrete. It refers specifically to the activity of labour itself, and the specific social and institutional relations of that activity.” She goes on to talk about how this might speak to the role of professionals – ie the subject of Olly’s text.

I find this approach helpful, because it makes clear that all work reproduces the wage relation – whether you’re an academic, information worker, or a kitchen hand – and that struggle around the activity of work is potentially more fruitful than trying to pinpoint which jobs are best to spend energy on.

In other words, what might be more constructive is to discuss the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of struggle against the wage relation, wherever that struggle may be, rather than focusing on ‘where’.

This relates to another aspect of this text I find troublesome. It feels like another anarchist text policing individuals within the movement for their decisions. It seems to place a lot of emphasis on the role of the individual anarchist. I get this, because that is what we can relate to in our own lives and our own organising, as anarchists. But this does not strike me as a way forward, but a further step inward.

Olly clarifies that we need a collective response to this on Redline, which is cool to hear.

Finally, I don’t agree with the ‘poverty of everyday life’ comment of Olly’s. Struggle around our everyday life is a must, but poverty often begets more poverty, and not struggle. I don’t like what this leads to (even if it is unintentional) – that the worse off people’s jobs are, the more they will struggle against it. If anything, history has shown that struggle on a collective scale tends to take place when things are good or improving for workers (a huge generalisation, I know).

I’m not sure if what I’m trying to say makes sense. I guess the short of it is that the potential for mass, collective struggle against the wage relation (and work) is all around us. We don’t need to narrow that to a particular type of work, especially when there may be important sites of struggle that is neglected in doing so. For example, could capital reproduce itself without childcare and daycare centres? I’m not saying this is a great example, but it is the type of question I’d love to discuss, rather than trying to monitor the further personification of capital by individual comrades.